In recent years, the field of pacing has seen huge advances with the advent of leadless pacemakers (LP), which are a revolutionary alternative to traditional pacing systems. Approximately 750,000 pacemakers are implanted worldwide annually.1 Pacemakers play a crucial role in restoring a normal heart rhythm and improving the quality of life of patients with bradyarrhythmia. However, the implantation of traditional pacemaker systems, although a well-established procedure, carries a risk of lead-related complications, including infection, lead displacement and venous occlusion.2

With the introduction of the new AVEIR LP (Abbott), many of the drawbacks of traditional pacemakers have been eliminated. The main advantages of this system are its retrievability, long-lasting battery and the elimination of lead- and pocket-related infections.3 The overall chronic retrieval success rate was reported to be approximately 88% among 241 patients who were implanted with LPs for 1–6 years.4

To use cutting-edge technology and provide our patients in Kazakhstan with a more sophisticated and patient-centred approach to pacing, we decided to perform AVEIR LP implantation. The clinical indications and potential benefits of this technology for our patients in Kazakhstan have been carefully studied by qualified medical professionals who have come together to explore this new direction.

This article presents our first experiences of implanting an AVEIR VR LP (Abbott), a milestone event that marked its debut in Central Asia. Our case series clarifies the technical details, complexities of the procedure and preliminary clinical outcomes of this ground-breaking accomplishment.

Methods

On 19–20 July 2023, a workshop on the implantation of the AVEIR VR LP (Abbott) was held in the JSC National Research Cardiac Surgery Center. This procedure was performed for the first time in Central Asia. The workshop consisted of a training session, in which an experienced engineer from Abbott provided instruction on the implantation procedure. In addition, the surgeon who performed all implantations received Abbott certification.

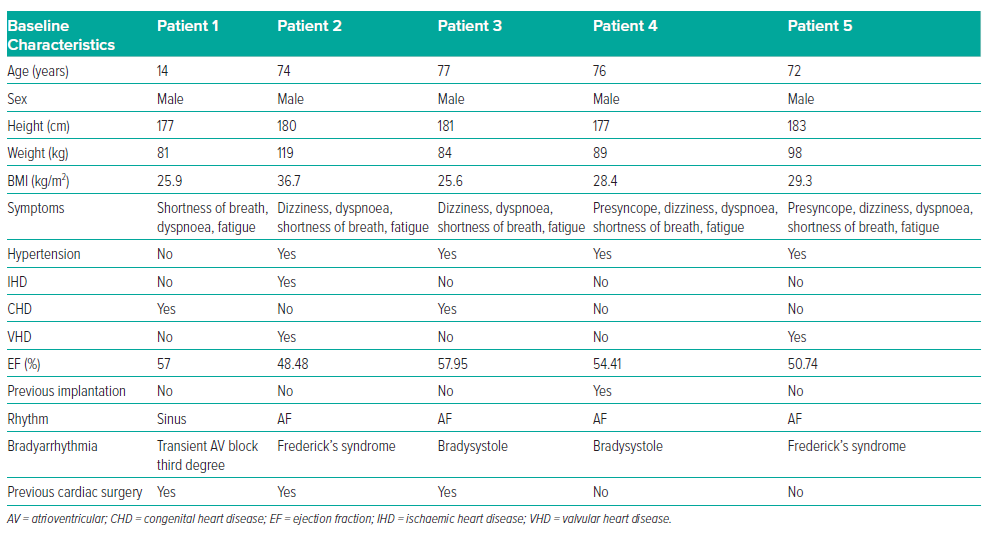

This case series includes five male patients, ranging in age from 14 to 77 years (mean age 62.6 years). The main patient complaints were presyncope, dizziness, dyspnoea, shortness of breath and fatigue. During patient examinations, indications for pacing were identified. Patient characteristics at baseline are summarised in Table 1. None of the patients were taking antiarrhythmic drugs at the time of the diagnosis of bradyarrhythmias and clinical manifestations started several months before hospitalisation. In four patients, bradyarrhythmia was present as a permanent form of AF; in half of these patients the bradyarrhythmia was present in combination with third-degree atrioventricular (AV) blockade, known as Frederick’s syndrome. All patients, except the child (patient 1), had arterial hypertension.

Patient 1 was 14 years old and had undergone surgical correction of tetralogy of Fallot. This child weighed 81 kg and was 177 cm tall, and was physically comparable to the adult patients. Patient 1 had been offered traditional pacemaker implantation, but the patient and his parents refused, agreeing only to LP implantation.

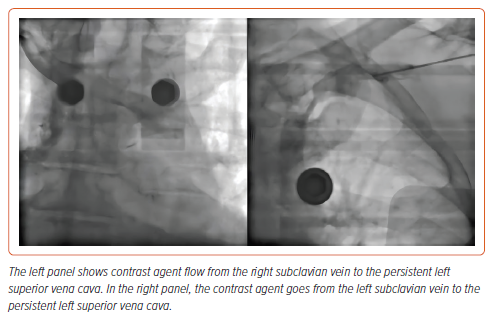

Patient 2 was diagnosed with class II obesity and had a combination of ischaemic heart disease and valvular pathology. A week before the index procedure, patient 2 underwent transcatheter aortic valve implantation and right coronary artery stenting procedures. In addition, patient 2 underwent venography (Figure 1), which detected persistent left superior vena cava. In this regard, the decision was made to implant an LP.

Patient 4 had comorbid conditions (i.e. kidney disease and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease) and had previously had a single-chamber pacemaker implanted due to bradysystolic AF. The pacemaker was later explanted due to pocket infection, and the electrode was cut, in another clinic. Because of patient 4’s comorbidities and age (76 years), there was a high risk of complications during the lead extraction procedure. Furthermore, patient 4 refused lead extraction but agreed to LP implantation.

All patients underwent a diagnostic ultrasound of the femoral vessels, which showed no evidence of stenotic lesions of the vessels, particularly of the femoral veins.

Before the LP implantation procedure, informed consent was obtained from adult patients and the parents of patient 1. The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the National Research Cardiac Surgery Center.

Results

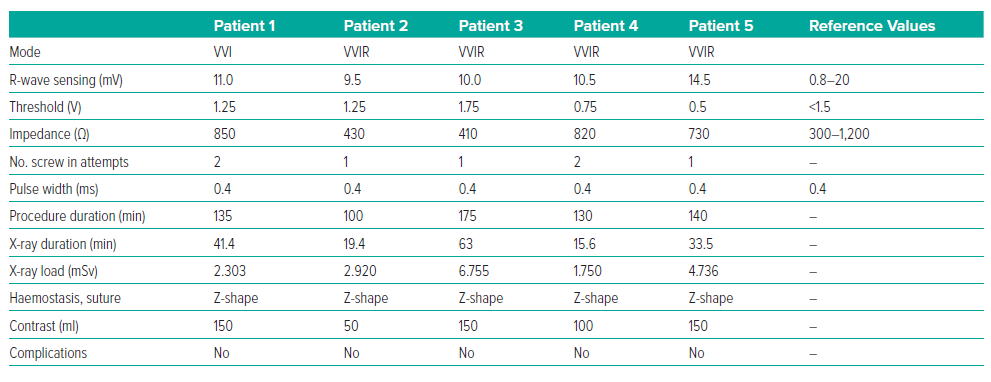

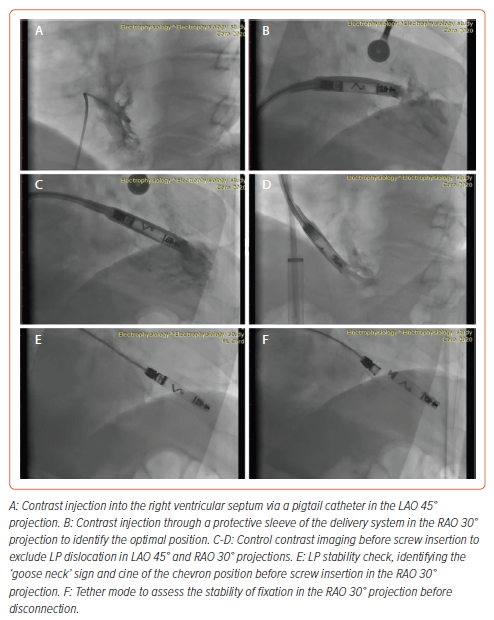

The LP implantation procedure was performed under local anaesthesia with 30 ml of 5% lidocaine. Sedation was provided by 2 ml of 1% fentanyl. A standard puncture of the right femoral vein was performed. Initially, a right ventricular pigtail catheter was used to deliver contrast to identify the interventricular septum. The LP delivery system was then advanced from the right femoral vein into the right ventricle in the right anterior oblique 30° view. The delivery system was then turned and advanced towards the interventricular septum in the left anterior oblique (LAO) 30° view. The position was confirmed by the introduction of contrast. The LP was screwed clockwise into the low interventricular septal position. The mean (±SD) number of screw in attempts was 1.4 ± 0.5. There was difficulty determining the optimal placement of the LP with good sensitivity (>0.8 mV) in the first three patients (Table 2).

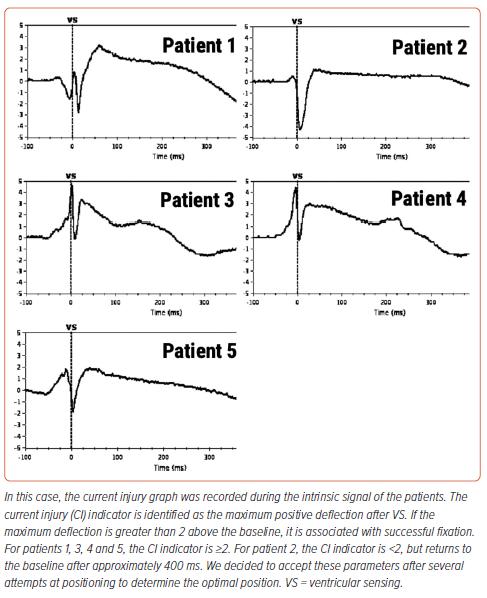

After installation of the pacemaker, a control check of the stimulation parameters was performed (Table 2). Because reference values for the AVEIR system and traditional pacemakers are the same, it was decided to use traditional reference values for R-wave sensing, threshold and impedance.2 In all patients, the stimulation parameters were within the reference range (Table 2). Because the radiological and stimulation characteristics were satisfactory, the LPs were left in position (Figure 2). An ECG after the LP had been screwed into the myocardium showed current injury, a curve line above baseline, which is the index of myocardial injury and one of the criteria of satisfactory fixation of LP (Figure 3). The delivery system was then disconnected from the pacemaker and the stimulation parameters measured again. A transthoracic echocardiogram was performed, and no signs of pericardial separation were detected. The puncture site was sutured with a Z-shaped suture. The day after implantation, an X-ray ruled out dislocation, and the stimulation parameters did not differ much from the initial stimulation parameters. All patients were discharged on the second day after implantation of the LP. One month later, all patients underwent a follow-up examination. The stimulation parameters at follow-up were acceptable (mean [±SD] impedance 530 ± 150 Ω, threshold 0.75 ± 0.25 V, R-wave sensing 11 ± 3 mV, pacing duration 0.4 ms) and all patients reported clinical improvement.

Discussion

The undeniable advantage of an AVEIR LP is the reduced risk of complications associated with the introduction of the electrode, which distinguishes it from pacemakers that require a lead and carry the burden of lead- and pocket-related complications, such as infections and dislocations.2,3,5 None of the patients in our cases experienced any of these issues, which potentially demonstrates that the AVEIR LP is a better solution than its counterparts that use electrodes. Our study indicates the absence of acute and delayed complications, highlighting the potential of this innovative LP system to address the common complications that often accompany the use of conventional pacemaker systems. The elimination of lead-related infections is a key advance in improving patient safety.

According to our statistics, the mean duration of the LP implantation procedure is 137 min (Table 2), which is much longer than the time required for the implantation of traditional pacemakers in our centre. However, we believe that with routine implantation, the procedural time is likely to be reduced and the LP shows promise in maintaining stable pacing parameters over time, potentially improving its long-term reliability over traditional systems prone to lead-related problems.

Limitations

This case series included a relatively small number of patients, which may limit the generalisability of our findings. In addition, because our study is a single-centre experience, our results may not fully reflect the broader population or differences in clinical practice. Furthermore, longer follow-up is needed to evaluate the durability and the sustainability of the pacing parameters and observed clinical outcomes. Moreover, the AVEIR VR interrogation process requires a specific Merlin programmer, which only supports this type of pacemaker and thus somewhat complicates the work of physicians.

Our study contributes to a growing body of data on the safety and feasibility of implanting the AVEIR LP. The historical value of the first procedures in Central Asia emphasises the innovative nature of the work. The collaboration of an interdisciplinary team and the careful evaluation of patients for selection demonstrate our commitment to advancing patient-centred care. The first five patients were treated as representative cases to pave the way for future LP implantations in Kazakhstan. Our centre is planning to include this technology in an effective protocol for the treatment of bradyarrhythmia and increase the number of procedures.

Conclusion

In conclusion, our experience in Kazakhstan implanting the AVEIR LP demonstrates its potential benefits in terms of reduced complications, patient comfort and potential improvement in quality of life. Although the limitations of the study must be acknowledged, our results are consistent with the growing enthusiasm for LP technology. As we move forward, it is crucial that larger multicentre studies with an extended follow up are conducted to further confirm the safety, efficacy and long-term benefits of this innovative pacing approach.