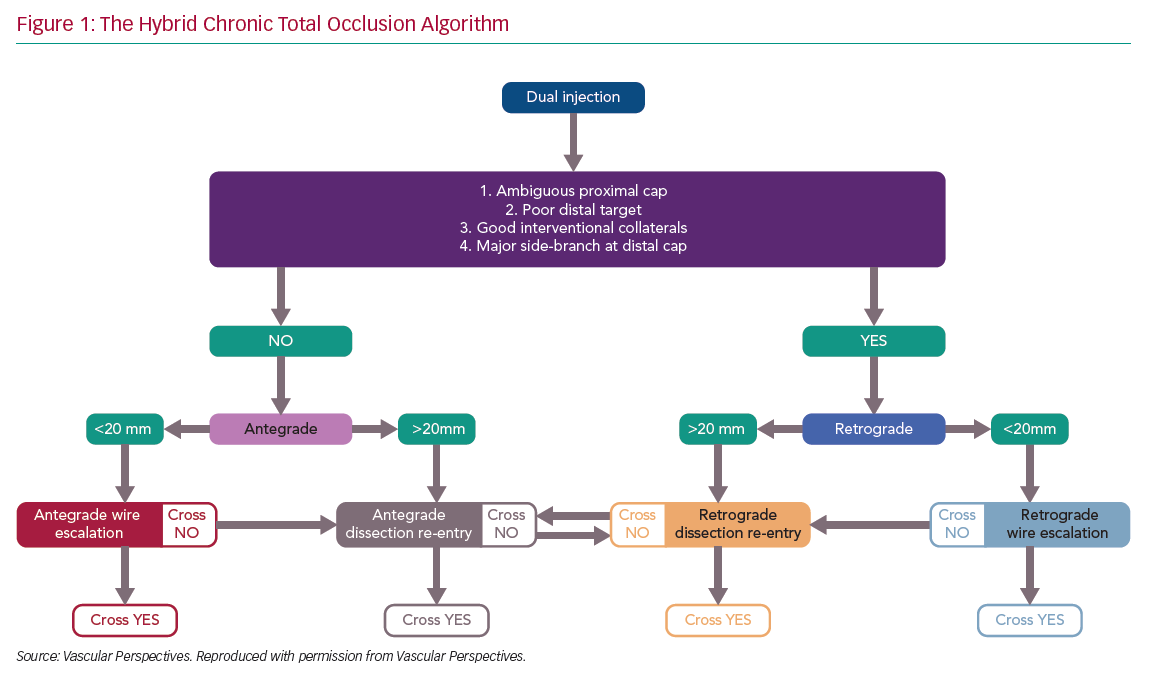

There has been rapid development in the techniques used for chronic total occlusion (CTO) percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) over the past decade, with success rates in experienced centres now exceeding 90%.1 This is in part due to advances in devices and techniques for CTO crossing, but also an improved understanding of strategy. The development of the ‘hybrid algorithm’ has improved success rates, safety and efficiency of these procedures across many countries (Figure 1).1–5

Registries consistently show that antegrade wiring (AW) is the most common strategy for crossing CTOs, particularly those of lower complexity.1,5 However, it is important to understand that to safely achieve a high success rate in CTO PCI, expertise in dissection and re-entry techniques (DART) and retrograde approaches are also required. This review will provide a contemporary update on antegrade techniques for CTO PCI.

Angiographic Assessment and Strategy Selection

A detailed understanding of the coronary anatomy is fundamental to successful CTO procedures. Some of the necessary information can be gained from a pre-procedure diagnostic angiogram, but dual catheter angiography is essential (with the exception of ipsilateral collaterals or bridging) to provide information about collateral filling, lesion length and vessel course. When acquiring dual catheter images, a wide field of view should be used, the camera should not pan and the run should be long enough to allow accurate assessment of collateral channels.

When interpreting the angiogram, there are a number of features that require assessment, and in turn help to guide procedural strategy.

The Proximal Cap

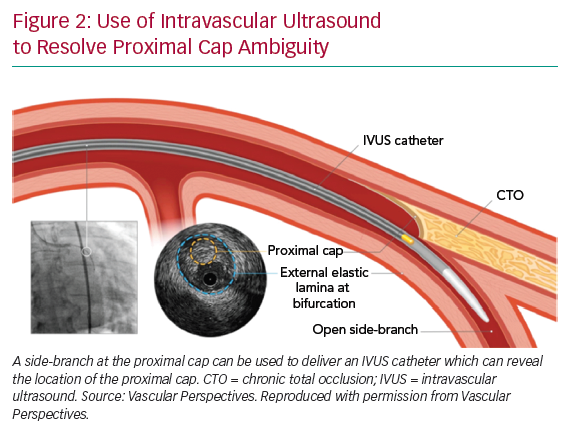

If the proximal cap is ambiguous (i.e. its location or the course of the vessel after the occlusion is uncertain), this is a point of jeopardy during the case. Adjunctive imaging with intravascular ultrasound (IVUS) should be considered to resolve anatomical ambiguity (Figure 2). Coronary CT can also provide information on location and morphology of the proximal cap, as well as lesion length, calcification and tortuosity.6

The shape of the cap is important: a tapered proximal cap may offer lower resistance to wire passage, and AW is more likely to be successful than in a CTO with a blunt proximal cap.7 The presence of a side-branch at a blunt proximal cap is common in long-duration CTOs. This may cause guidewires to deflect into the side-branch, making AW more challenging.

The Chronic Total Occlusion Body

Lesion length progressively increasing >20 mm makes intimal wire passage less likely and increases procedure duration.8 This will lead many operators to DART procedures primarily. A heavy burden of calcification and vessel tortuosity are additional features that confer complexity and make it more likely that DART may be required.1,5

The Distal Cap and Landing Zone

The vessel beyond the distal cap and before the origin of a major side-branch is known as the distal landing zone (LZ), referring to the area for potential re-entry during antegrade dissection and re-entry (ADR). If the distal cap is at or near a bifurcation of a significant side-branch, the chance of dissection extending across the branch and causing occlusion is increased, making ADR a less favourable strategy. Similarly, inadvertent extraplaque wire passage at the distal cap during AW can have the same effect. If there is a heavily diseased LZ in close proximity to a major bifurcation, a primary retrograde strategy is indicated, provided this can be achieved safely.

Collateral Supply

Collateral vessels supplying the distal vessel facilitate visualisation of the distal target during antegrade procedures, and also open the possibility of a retrograde approach. The source of the collateral should first be identified, and then the course of the collateral considered (epicardial or septal). The diameter of the collateral, tortuosity and angle of entry and exit from vessels are other important features in determining whether the collaterals are suitable for use as a retrograde conduit.9 When visualisation of a collateral channel is challenging, selective imaging using a microcatheter may be considered.

Operators should be mindful that retrograde procedures are associated with increased complications from the procedure (although selection bias may contribute to this observation) and the risk associated with perforation is highest when using epicardial collateral channels.3,10

Procedural Setup

With advances in equipment and technique, most CTO procedures can now be carried out through 7 French guide catheters. There has recently been a move towards bilateral radial access. The use of appropriately sized catheters, which provide a high degree of passive support, (typically Voda Left, XB or Extra Back-Up curves for the left coronary, and Amplatz Left or 3D curves for the right coronary) has little downside, while having the advantage of avoiding the morbidity and mortality of vascular complications from femoral access.11 In the Registry of CrossBoss and Hybrid procedures in France, the Netherlands, Belgium and United Kingdom (RECHARGE), 24% of cases were performed using only radial access. This had no impact on procedural success compared with transfemoral access, irrespective of lesion complexity.12

After engagement of the donor guide, we recommend that a workhorse wire should routinely be placed in the donor vessel. This maintains the catheter position, allows easy engagement and disengagement and importantly also expedites treatment of any donor vessel injury (which can cause rapid deterioration in the context of a contralateral CTO).

Antegrade Wiring

AW is a technique where a guidewire penetrates the proximal cap of the CTO and aims to remain intraplaque before entering the distal true lumen. In reality, the wire often passes in and out of the vessel extraplaque during AW, often unrecognised angiographically.13–15 AW is most likely to be successful where there is a clear, tapered proximal cap and the occlusion is short (<20 mm). Where these conditions are not met, a primary AW strategy may still be appropriate, but operators should understand that the probability of successfully completing the procedure is lower and should remain flexible to changing to an alternative strategy if progress is not being made.

Initial Wire Selection

AW has traditionally been described as an escalation of wire tip load until the lesion is crossed. While this is effective for crossing some CTOs, it is more efficient to select wires based on their suitability for a particular task within the procedure. It should also be noted that any wire should be used in combination with a microcatheter. Various microcatheters are available, although a comprehensive overview of their properties and application is beyond the scope of this article.

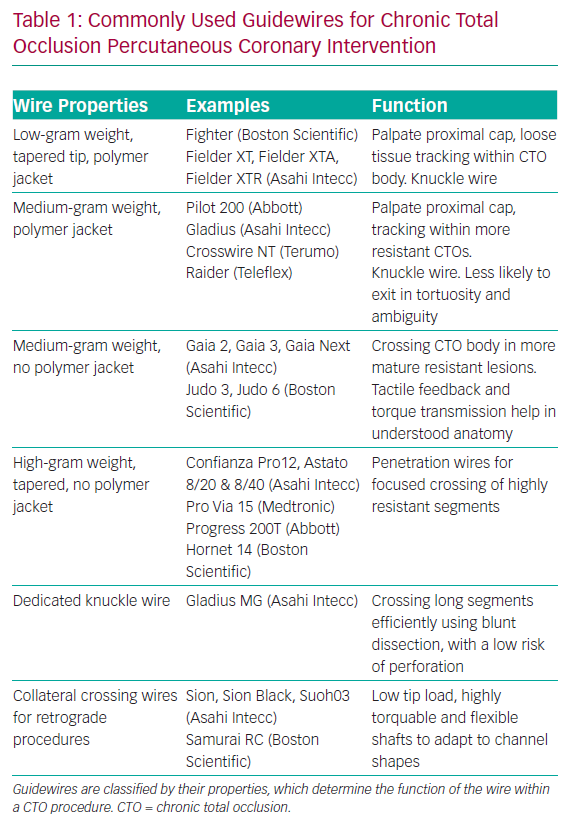

A knowledge of guidewires, their individual properties and the tasks they are used for is therefore fundamental to AW success. A detailed description of each wire is outside the scope of this review, but it is helpful to group CTO lesion crossing wires into categories based on their properties and functions. Some newer guidewires are outlined in Table 1.

With this understanding, the choice of initial wire for AW should be dictated by the anatomy of the CTO, in particular the proximal cap. If the cap is tapered, a low- or medium-tip load wire with a polymer jacket is a good choice, as the cap is likely to be of relatively low resistance and these wires can track loose tissue within the CTO body with a relatively low risk of exiting the vessel.

Factors that should prompt consideration of a penetration wire are:

- Blunt proximal cap – in longer-duration CTOs, the proximal cap tends to be blunt due to prolonged exposed to systemic arterial pressure, causing formation of dense fibrous tissue.

- Heavy calcification at the proximal cap.

- Presence of a side-branch or bridging collaterals at the proximal cap that often cause softer, jacketed wires to prolapse or deflect away from the cap.

A penetration wire (i.e. a Confianza Pro 12; Asahi Intecc) is well suited to crossing a short occlusion, with a blunt cap and with little tortuosity in the CTO body. It is important to understand that penetration wires can easily exit the vessel architecture, and are therefore not suitable for crossing long CTO segments, especially where the course of the vessel is ambiguous or there is established within-CTO tortuosity.

Crossing the Chronic Total Occlusion Body

Once a penetration wire has crossed the proximal cap, it is safest to advance the microcatheter into the CTO and exchange for a less penetrative wire, unless the CTO segment is very short and straight. This principle of exchanging wires based on CTO resistance is known as ‘escalation/de-escalation’, and the overriding principle is of safety, provided that progress is being made.

Before advancing a microcatheter (or other equipment) over a wire, the position of the wire must be confirmed. Medium- and high-gram weight wires, especially those without polymer jackets, can exit the vessel architecture. Wire exit on its own is usually of little clinical consequence; however, advancement of secondary equipment beyond the adventitia will usually lead to significant perforation.

Wire position can be confirmed by taking a number of orthogonal views to check the wire is within the vessel architecture in all projections, and is seen to be ‘dancing’ in synchrony with the vessel. A retrograde contrast injection from the donor guide can also be helpful. Antegrade injections are less likely to provide additional information and may hinder attempts at DART if there has been extraplaque wire passage.

Once the wire position has been confirmed in the distal true lumen, the microcatheter should be advanced beyond the distal cap and the wire exchanged for a workhorse wire, which can then be used for the remainder of the procedure.

There are a number of other wires that have specific functions within CTO procedures. When starting a knuckle to facilitate dissection, a soft- or medium-tip load polymer jacketed wire is usually used, although dedicated knuckle wires are now coming into routine use (Table 1).

Antegrade Dissection and Re-entry

ADR is a technique where the guidewire and/or equipment intentionally pass into a dissection plane before re-entering the distal vessel lumen at or beyond the distal cap. The technique has two main indications, first as a primary strategy for crossing long or complex CTOs, and secondly as a bailout following inadvertent extraplaque wire passage during AW that cannot be resolved.

Wire-based Re-entry Techniques

Many AW procedures (~10%) may represent a form of inadvertent ADR, although the wire typically regains the true lumen close to the distal cap.13

Subintimal tracking and re-entry (STAR) was the first dedicated ADR technique to be described.16 This involves passage of a looped or ‘knuckled’ guidewire into a dissection plane and advancing it until it enters the distal lumen, often at the site of a bifurcation, risking loss of branches. The mini-STAR technique is when an attempt is made to wire the occlusion as far as possible before entering a dissection plane,17 thereby theoretically minimising the length of extraplaque wire passage. Mini-STAR does not overcome the fundamental downside of STAR: that re-entry cannot be controlled. The medium- and long-term outcomes from these techniques are poor,18–20 and at present, they are only used in two circumstances: when a guidewire inadvertently re-enters the lumen close to the distal cap during ADR or as a bailout manoeuvre as part of an investment or CTO body modification procedure that aims to facilitate a later second attempt.1

Limited antegrade subintimal tracking and re-entry uses targeted re-entry by advancing a microcatheter within a dissection plane and attempting wire-based re-entry beyond the distal cap.21 The subintimal wire is exchanged for a penetration wire with a large primary bend, and this is directed towards the true lumen to re-enter. This technique is also not reproducible and has largely been abandoned since the development of dedicated re-entry equipment for ADR.

Another non-targeted technique for ADR has recently been reported.22 Antegrade fenestration and re-entry (AFR) causes disruption within the vessel extraplaque by inflation of a 1:1-sized balloon through the CTO segment. This aims to create tears within the vessel media, thus allowing a soft polymer wire to cross fenestrations and reach the distal true lumen. The experience of this technique is largely confined to a single centre with six successful cases reported so far. Given the established role of ballooning the subintimal space for investment and a lack of reliable ability to re-enter the distal true lumen in a long experience of these procedures,1 extensive data about the reproducibility of AFR and longer-term outcomes will be required. Most likely, STAR and AFR will be reserved for bailout manoeuvres when targeted re-entry cannot be facilitated by targeted ADR or retrograde procedures.

Device-based Re-entry Techniques

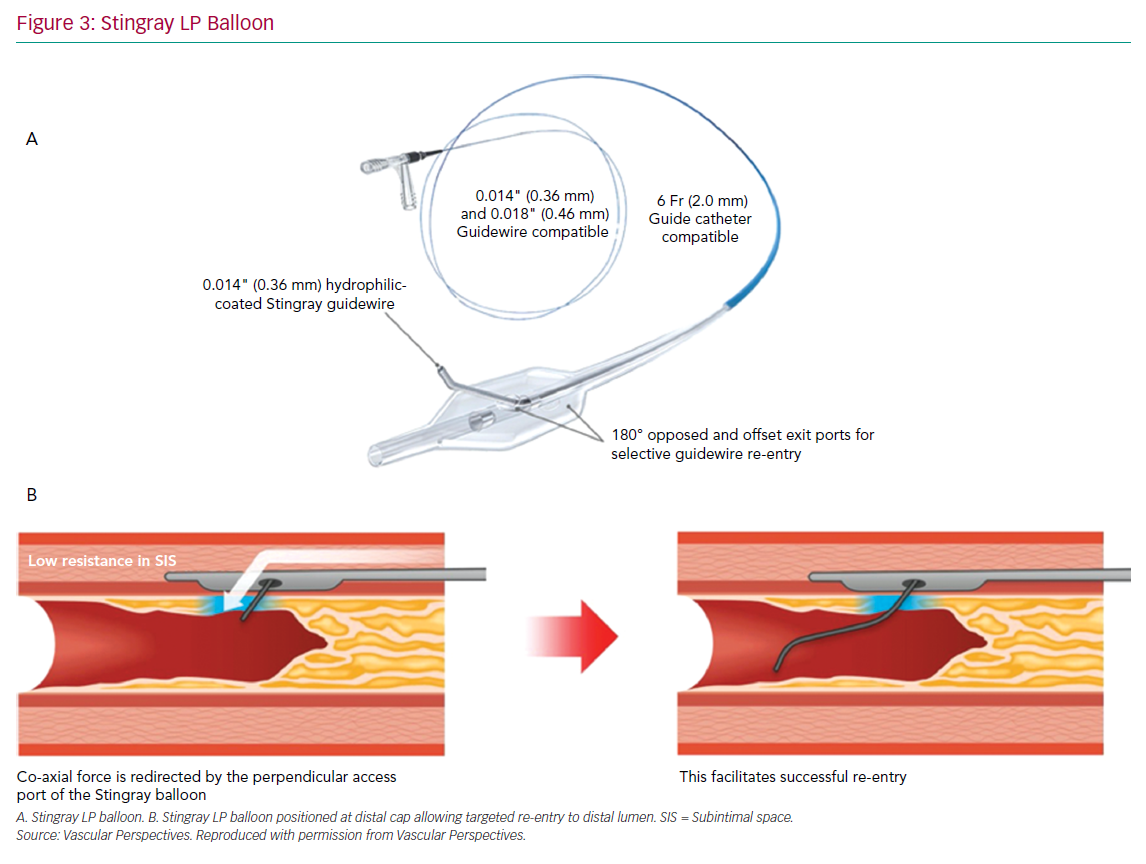

The CrossBoss and Stingray system (Boston Scientific) continues to form the mainstay of targeted re-entry devices. The CrossBoss is a blunt tipped dissection catheter that will track through intimal plaque or create a controlled extraplaque dissection that facilitates delivery of the Stingray LP balloon beyond the distal cap (Figure 3).

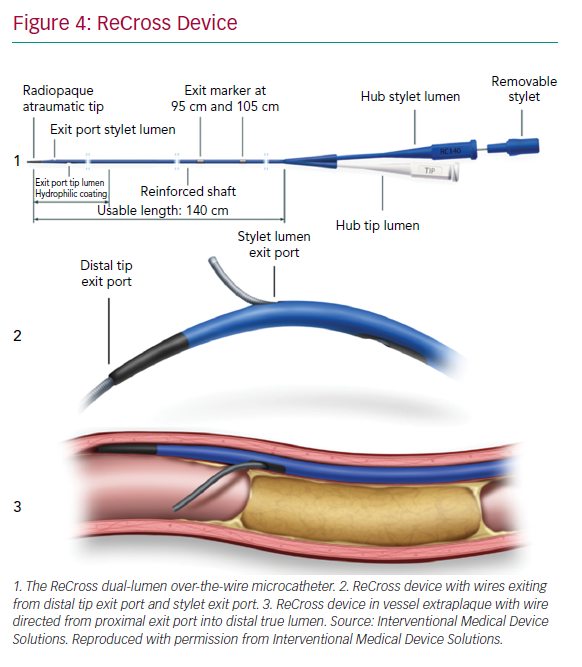

The ReCross device (IMDS) is an over-the-wire, modified dual-lumen microcatheter. It has two exit ports close to the distal end of the device, oriented at 180o from each other, thereby providing some degree of control in guidewire redirection (Figure 4). At present, experience with the device is limited, with no published case series.

A primary ADR procedure is typically applied to cross long and/or ambiguous CTOs where the proximal cap is well defined and there is an LZ proximal to important side-branches.23 After crossing the proximal cap, a balloon in the vessel extraplaque is used to introduce a guide catheter extension as a standard step. The Trapliner (Teleflex) allows the most efficient exchange of equipment for ADR, while also preventing haematoma formation. A knuckle wire and microcatheter can then be advanced across the CTO segment. When approaching the LZ, many operators will use the CrossBoss to create a smaller dissection plane for the last 20–30 mm to minimise haematoma formation. The Stingray LP balloon is then delivered, inflated and the correct orientation for re-entry found on fluoroscopy. Wire choice for re-entry has evolved since the introduction of the device; the Stingray wire has a small microbarb at the tip. This is helpful for re-entry when the balloon is close to a healthy distal LZ. However, in the presence of a large burden of atheroma between the balloon and lumen, it may be less effective. In this circumstance, many operators prefer a tapered penetration wire (i.e. Confienza Pro 12 or Astato 8/20 [Asahi Intecc] or Hornet 14 [Boston Scientific]). After re-entry to the distal true lumen and removal of the Stingray LP, the penetration wire is exchanged for a workhorse wire via a microcatheter to safely complete the procedure.

When the wire inadvertently passes into a dissection plane and beyond the distal cap during AW, we advocate an early switch in strategy to bailout ADR, if the anatomy is suitable. In this setting, the CrossBoss is often not required. The antegrade microcatheter can be advanced to the LZ and a MIRACLEbros 12 wire (Asahi Intecc) used to deliver the Stingray LP balloon or ReCross for re-entry. By minimising the steps in the procedure, this increases procedural efficiency without compromising safety.

Troubleshooting During Antegrade Dissection and Re-entry

Troubleshooting CTO lesions is an important skillset. In the following section, we describe some common challenges during ADR and how these can be resolved.

Impenetrable Proximal Cap

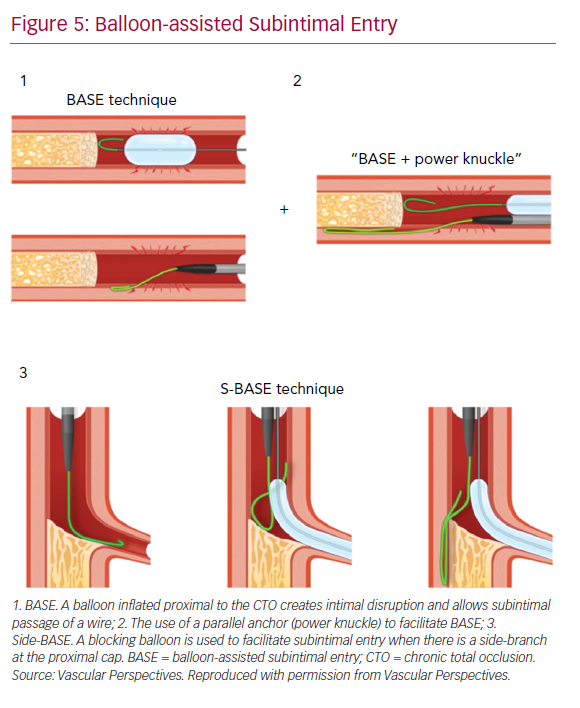

With impenetrable proximal caps or unresolvable anatomical ambiguity, one solution is the use of balloon-assisted subintimal entry (BASE) and a parallel anchor (power knuckle; Figure 5).24 A balloon, sized 1:1 with the vessel, is inflated proximal to the CTO to create intimal disruption. A microcatheter is then positioned alongside and the balloon inflated to trap the microcatheter. This increases support and allows passage of the knuckle wire into a dissection plane.

When a side-branch is present at the proximal cap, a modification of this technique (side-BASE) can be used.25 A blocking balloon is positioned in the side-branch causing deflection of the knuckle wire into a dissection plane (Figure 5).

Equipment Enters a Side-branch

When advancing a knuckle or CrossBoss, it is important to confirm it is moving in synchrony and in plane with the main vessel architecture. If this is not the case, the most likely explanation is passage into a side-branch. This can be resolved by retracting the equipment and redirecting a wire past the side-branch before advancing the CrossBoss or microcatheter over the wire until it is beyond the side-branch. At this point, blunt dissection can be resumed. If this is not successful, a dual-lumen catheter or a blocking balloon placed in the side-branch can aid redirection.

Haematoma at the Landing Zone

Extraplaque haematoma at the LZ is a common failure mode of ADR. The use of a guide catheter extension within the proximal CTO to prevent inflow, avoiding extensive dissection beyond the distal cap with knuckled wires, and/or using the CrossBoss close to the LZ, all help reduce haematoma formation. Additionally, we recommend routinely aspirating from the end hole of the Stingray balloon prior to attempting the puncture.

The subintimal transcatheter withdrawal technique can also be used to reconstitute the LZ when there is reduced filling due to haematoma.26 With the Stingray balloon in place, a second wire is advanced into the vessel extraplaque, and an over-the-wire 1:1-sized balloon is delivered and inflated, blocking any inflow to the vessel. A syringe is then used to aspirate haematoma via the tip of the over-the-wire balloon, and puncture re-attempted after the distal vessel reconstitutes.

The Role of Intracoronary Imaging

There is now clear evidence that the routine use of intravascular imaging significantly reduces target vessel failure in non-occlusive disease.27,28 IVUS is preferred over optical coherence tomography for CTO PCI, as it avoids the need for high-pressure contrast injection, which can create and propagate dissection. Many operators will be familiar with the use of IVUS for stent sizing, identifying stent LZ and assessing stent apposition and expansion, and this is invaluable in optimising results in CTO PCI. We advocate the liberal use of IVUS during CTO PCI, stent deployment and optimisation to maximise procedural durability.

In addition, IVUS can determine the course of the wire through different vascular compartments. It is important to know where the wire is in the false lumen and how this relates to side-branches that need to be preserved. This is particularly important in ADR when the site of re-entry is close to a major bifurcation. If a wire has crossed a side-branch in a dissection plane, stenting will result in loss of that branch, and potentially procedural MI.

Complications and Outcomes Following ADR

Contemporary registries show low complication rates from CTO PCI.1,3,29 When comparing complications between different strategies, there is a higher rate of perforation and major adverse cardiovascular events (MACE) in patients treated with DART, and especially retrograde procedures, compared to AW.3,29,30 This reflects the increased complexity of CTOs that require the application of DART, including longer lesions, higher Japanese CTO scores and an increased proportion of post-coronary artery bypass graft cases.

The higher rate of target vessel failure with STAR has led to some concern that stenting extraplaque in the vessel leads to poorer outcomes than intraplaque stenting.18,19 Modern ADR using targeted re-entry, with a focus on preserving all important side-branches, is a different procedure. There is no evidence to suggest that this has any adverse long-term clinical consequences.13,29–31 Vessel healing and stent coverage appears to be unaffected by extraplaque stenting on optical coherence tomography follow-up in the largest series reported to date.13 It is unsurprising that more complex lesions that require DART and longer stent lengths are associated with an increase in both target vessel revascularisation and MACE.13 This is true of every PCI, and is due to the disease burden and stent length more so than the technique that is applied during the case.

Conclusion

Advances in equipment and technique have undoubtedly led to improvements in the field of CTO PCI, and operators must familiarise themselves with these to achieve good outcomes for patients. It is equally important to understand when to use each of these within a case, as developments in procedural strategy have had the biggest impact in improving outcomes from CTO PCI. AW remains the predominant strategy for crossing short CTOs of lower complexity. However, many CTOs can only be opened with a dissection-based strategy, and ADR offers a safe and efficient means to achieve this when used in appropriately selected cases.