Interventional cardiology is a demanding subspeciality, both while training and throughout consultant life. Specifically, long working hours, regular out-of-hours commitments and high risk, technically challenging procedures result in a stressful working environment. Concurrently, there is an appropriate expectation that interventional cardiologists should act with civility and courteousness. Recent data have highlighted a concerning prevalence of bullying behaviour towards cardiology trainees and there is evidence that the subspeciality of interventional cardiology has a particular problem in this regard.1 Therefore, in 2022, the British Cardiovascular Intervention Society (BCIS) established a focus group to specifically address the issues of bullying and training culture within our subspeciality.

This BCIS Focus Group position statement is designed to provide both trainers and trainees within our subspeciality a framework that offers advice and insights into how suboptimal interactions can be avoided and managed between trainers and trainees. Our aim is to produce guidance that avoids the adversarial ‘us and them’ culture that can be stimulated by unbalanced, negative feedback; approaches this challenging issue from the point of views of both trainee and trainer; and is complementary with the Joint British Societies position statement on inappropriate behaviour.2

Our Core Concepts

- Unprofessional behaviour has a deleterious effect on patient safety.3

- We acknowledge that bullying has no place in interventional cardiology, and that we have a responsibility to address this problem.4

- Unfortunately, there is no universally agreed definition of bullying. For the purposes of academic endeavour such as writing peer-reviewed papers, whether reports of surveys of trainees’ experiences or consensus statements for suggested ways to improve, these activities are inevitably hampered by a lack of scientific precision. This does not negate their potential value.

- The majority of trainers want to deliver positive learning experiences. Therefore, it is likely that most suboptimal interactions between trainers and trainees will be modifiable with low-level intervention if these episodes can be identified, discussed and reflected on in an open and constructive manner among those receptive to change.

- For trainers who exhibit recurrent bullying behaviour, our recommendation is that they are reported to their employer to be dealt with using pre-established, robust disciplinary measures.

The Scope of the Problem

Defining bullying is challenging, so that a pure and scientifically precise definition within healthcare is unfortunately not attainable. However, the concept of a bully can be encompassed by the Cambridge Dictionary definition as: “Someone who hurts or frightens someone else, often over a period of time, and often forcing them to do something that they do not want to do.”

The prevalence of bullying within cardiology is well documented. Between 2017 and 2020, more than 10% of UK cardiology trainees reporting bullying in the 4 weeks prior to being surveyed; this is almost twice the average across all medical specialities (12.3% reported in cardiology and 6.9% reported in medicine).4,5 Importantly, the rates of reported bullying were even higher in those with protected characteristics, an observation that is consistent with the experiences of the consultant body.6

Bullying not only has a profound negative effect on the performance and wellbeing of the individual and wider team, but also impacts on medical error rates and patient safety.7–10 While rates of bullying within cardiology are higher than other medical specialities, it is important to recognise the high volume of out-of-hours work centred around critically unwell patients in life-threatening, time-critical scenarios. This, coupled with historic working patterns in many centres across the UK that require the continuation of scheduled day-time clinical activities post on call, are likely to be contributing factors. Mandatory rest periods following flight time within the aviation industry are well documented, and not only result in error reduction, but also improvements in working relationships.11 Surgical specialities with similar working patterns as seen in interventional cardiology also report a high prevalence of bullying. Reported rates are highest within general surgery and paediatric surgery, which is comparative to cardiology, and in a similar pattern, most frequently occur within the operating theatre.5,12

While repeated instances of wilful bullying should not be tolerated, the BCIS recognises that the majority of trainers want to deliver positive, meaningful learning experiences to trainees. Despite this, on occasion, some trainers will fall short of the standards expected of them. It is likely that trainers involved in these circumstances will be motivated to modify their behaviour if the situation is approached in a constructive manner. If trainers are accused of bullying, there is a very real risk that they may disengage from future training interactions. Disengagement of trainers in a centre is in nobody’s interest because it reduces training opportunities for trainees and risks their removal by the Deanery, which, in turn, impacts on the delivery of care. Thus, the aim should be to bring trainers and trainees closer together to improve training through managed interactions without alienating either party.

Setting Expectations

Current training involves frequent rotation between hospitals and multifaceted weekly timetables. With the fragmentation of the historic structure of ‘the firm,’ consultants and trainees may not work with each other as frequently as they did in the past.13

Historically, training was based upon an apprenticeship model that allowed for familiarity within a team, at the expense of unacceptable hours. In the current system, reduced familiarity means that trainees may not be aware of the expectations of individual consultants in terms of patient assessment, preparation and follow-up. This is often a situation that can exacerbate tensions within the team. Therefore, it is important for consultants to clearly and positively establish their expectations for a list, and for trainees to make sure that they understand the way that the trainer likes to run their list and procedures. For example, details regarding how the trainer likes their lists to run may include specific procedural aspects, such as a preference for radial cocktail, arm angiogram, etc. We recommend trainees take the lead in these settings and are proactive in seeking out the supervising clinician prior to the list to establish operating expectations along with discussion with their senior peers who have greater previous experience of working alongside specific consultants.

Additionally, as we move towards an era where the experience of trainees emerging from each stage of training may be lower than in the past (through mandated dual accreditation with general internal medicine and adoption of the new curriculum), trainees may require more support. This does not mean they will fail to achieve procedural competence in the future, but renders clear expectation setting ever more important and this should be a two-way dialogue between the trainer and trainee.

Many misunderstandings in the catheter lab can be averted by a clear, brief summary of current level of experience, limitations, expectations and trajectory when trainees work with new trainers. This will help trainers to adjust expectations and levels of supervision accordingly and personalise opportunities to the individual, including those in senior interventional fellowship positions (ST6–ST8) who may not have the experience of their historic counterparts. Acknowledging that experience levels in trainees may be lower than in the past, the timely recognition of potentially major complications may be affected. In these situations, urgent intervention from the supervising consultant is necessary and may be accompanied by unintentionally curt comments. A full debrief should occur at the completion of the case and learning points for both parties discussed.

Trainees should ideally also be able to set training goals that include all types of clinical encounters, for example, at the start of a placement, the beginning of a catheter lab list or on a ward round, allowing for some circumstances, such as clinical emergencies, when patient care must be prioritised. Finally, trainees should feel comfortable in identifying mutually convenient opportunities to discuss possible workplace-based assessments, which are an important factor for their training progression.

The Delivery of Feedback

Mentorship is crucial to cardiology, especially in interventional cardiology training, and a central part of this is the delivery of timely and constructive feedback.14 This can be challenging: the delivery of feedback is one of the most common scenarios in which friction between trainee and trainer can occur and both parties need to be mindful of this. The development of an ‘us and them’ culture risks separation of the aspirations of trainees and trainers.

Both trainees and trainers should receive regular constructive feedback delivered with the intention of continued positive professional development: this is central to the UK mentorship training model. Feedback to trainees in relation to practical procedures, such as observations made during coronary intervention, is best delivered immediately if important for procedural safety. Otherwise, more general comments and feedback can be delivered in a variety of ways and the trainee and trainer should agree at the start of each procedural list how they prefer this to be done. For example, some trainees may have no concerns with the consultant making suggestions from the control room, while others will prefer it if their supervisor is scrubbed beside them or stood close by, thereby delivering suggestions that will not be overheard by the wider catheter lab team. An individualised approach is important to enhance the educational experience and minimise tensions.

Feedback interactions are most successful when they seek to address specific issues rather than to deliver broad, general comments. Several successful methods of feedback delivery have been widely accepted, including the Pendleton method, One-Minute Preceptor and feedback sandwich.15 Furthermore, the trainer should always ask whether the trainee wishes to make any feedback comments of their own, as these interactions should be framed as a mutual learning dialogue, shared between two intrinsically motivated parties rather than a one-way didactic experience, which can be belittling and reduces opportunities for engaged, reflective practice.

There is clear evidence that feedback delivered in a harsh, overly critical, or aggressive manner yields negative reactions and suboptimal learning.16 However, while this is intuitive, it is important to acknowledge that the threshold for considering feedback as harsh, overly critical or aggressive may vary between individuals. It is the responsibility of both trainers and trainees to discuss and agree their expectations of feedback delivery and to adjust their behaviours accordingly. A model that encourages two-way dialogue offers instant feedback to both parties and offers both the opportunity to modify their future interactions to avoid unnecessary friction.

Feedback delivery often incorporates critical learning messages regarding patient safety. Trainees must recognise that the highlighting of an error or deficiency in their management of a patient may result in a negative emotional response, however expertly it is handled.

Furthermore, the ideal circumstance and time to deliver any feedback varies with the scenario and individuals involved. If the feedback does not need to be immediate, there are key factors that can be chosen by the trainee with the aim of offering them autonomy and security in a relationship in which there is a pre-existing power imbalance. For example, whether they would like the feedback conversation to occur alone with the trainer or with a third-party present, in an office or a neutral venue, etc. Negative feedback should ideally not be delivered while standing in a busy corridor, on a large ward round or on an open Teams/Zoom call.

Finally, both trainers and trainees should reflect upon what actually constitutes ‘negative’ feedback. Learning from mistakes and suboptimal patient care episodes is a key component of becoming a good doctor, a principle that does not stop when we become consultants and therefore trainers. Highlighting such events should not therefore be considered inherently negative by either side.

In contrast, the style and nature of the feedback may be considered negative by the trainee, and this represents a learning opportunity for the trainer if they can be provided an opportunity to consider alternative approaches. That is the shift in culture that we seek to promote. While we acknowledge that the current NHS environment places significant time constraints on trainers and trainees to achieve this goal, we strongly encourage departmental managers to facilitate the inclusion of formal protected time in job plans, within which interaction with trainees – including two-way feedback – can be pursued regularly. This will not only have a positive effect on the trainer-trainee relationship but also improve working practices for the future and thus patient safety.

Behaviours of Interventional Trainees and Trainers

UK interventional trainees and consultants are highly regarded globally and should strive to be ambassadors for UK interventional cardiology. Both should act with diligence and commitment, and their behaviours in and out of the workplace should reflect this.

It is imperative that both trainees and trainers address their own wellbeing, particularly during high stress times, for example after busy on-call days/nights, stressful catheterisation laboratory lists or unexpected complications. It is often in these times of stress when bullying and undermining behaviours can occur. There are several potential ways to mitigate suboptimal interactions at these high-risk times.

Firstly, trainers should identify when they are feeling vulnerable to stress. Once identified, they may choose to let their colleagues in the team know how they are feeling. For example: “I’m not at my best this afternoon, I’m afraid, because I was up all last night,” “sorry if I’m being grumpy, but I am still feeling sensitive about the patient who died yesterday,” or even “I’m sorry, but I’ve had a bad run of complications and was on call overnight, do you mind if I provide closer supervision than I normally would?”

Ultimately, consultants providing transparency on workplace stresses will almost always be met with concern, compassion and understanding by the wider team, including trainees. While communicating these feelings is clearly important, it does not provide an excuse for anyone to act poorly towards others. Should responses or comments be made in the heat of a stressful moment in a list or procedure, which is going to happen sometimes, we strongly encourage the trainer to make a sincere apology once the stress has settled, perhaps during a break between cases or at the end of the list. It is equally important that feedback about a procedure should be made in as stress-free and constructive an atmosphere as possible in order to have optimal value.17,18 We encourage all catheter lab team members to recognise when tensions are running high and to use this opportunity to take a break when possible and offer support for your colleagues where appropriate.

Interaction with Other Specialities

While it is well recognised that cardiology trainees are frequently subjected to bullying behaviour, primarily by consultant cardiologists, cardiology trainees themselves have a historical reputation for adopting poor behavioural patterns when interacting with other specialities.19 Each cardiologist has a responsibility to reflect honestly on their personal standards in this regard. It is imperative that change in relation to this occurs at all levels, and current cardiology trainees should be encouraged to reflect on and act to improve these data, in line with the consultant trainer body as per the aims of this document.

Methods of Reporting and Handling Episodes Perceived as Bullying

There is no doubt that action is needed to address the worryingly high rates of reported bullying in interventional cardiology. This requires a process in which trainees feel comfortable to report episodes they are concerned about, without fear of retribution. It also requires that both trainers and trainees have the opportunity to reflect on the particular circumstances of the interaction, on how they might modify their future behaviours and – where appropriate – offer an apology.

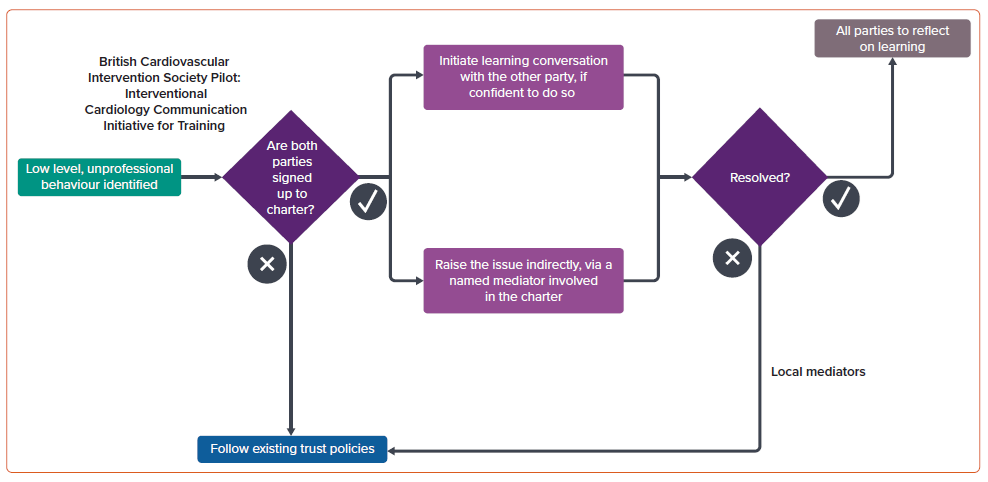

A number of potential alternative strategies exist. One option, currently being piloted by the BCIS Training Culture Focus Group, is a Departmental Charter process (Figure 1 and Supplementary Material Appendix A). The central premise of this initiative is that trainees and trainers within a centre sign up on a voluntary basis to take part in a process in which they agree to abide by a code of conduct.

The key element is that all parties agree to discuss any episode of suboptimal behaviour openly, either together or with a third party in attendance. The aim of the discussion is to review the interaction to analyse which elements were suboptimal and why, in the spirit that there are often learning points on both sides. Trainers in such a system sign up to avoid confrontational discussion and to be open to modify their future behaviour patterns where they agree this would be helpful. A qualitative follow-up process to assess the effectiveness of this amnesty system will be built into the pilot.

Access to Resources to Help Train Trainers

Training other people is a skill, and individuals vary in their natural ability to do so. It is therefore everyone’s responsibility to ensure that they are sufficiently trained in this area, as is expected in every other aspect of clinical and academic work. For example, there are several Tomorrow’s Teachers courses available. These may be included in Deanery leadership courses and have a general approach tailored to all medical and surgical specialities.20 Similar courses are also available nationally within formal educational accreditation.21

Both interventional cardiology trainers and trainees should attend courses on human factors and performance management in stressful situations. Many of these courses are available through NHS providers, or alternatively through airline providers and the military.22,23 Working in the catheterisation laboratory has many parallels with the airline industry, where it is clearly acknowledged that stress and associated poor communication impacts on performance. Importantly, training in human factors and crew resource management has been shown to improve patient outcomes.24

The BCIS has begun evaluating available human factor courses across the UK, with the intention of offering such courses to its members in the future. Appropriate courses should cover important topics, such as error and blame, mental processing, situational awareness, decision-making and communication. We feel that these courses would be invaluable to trainers, trainees and wider allied health professional members of the catheterisation laboratory team. This is particularly the case if they can be attended as a team, which the BCIS is keen to facilitate.

Conclusion

There is an acknowledged problem with bullying within UK interventional cardiology that needs to be tackled. It is our position that the solution – with the exception of the repeat offender – lies in trainers and trainees tackling the problem together. We advocate for processes that assume that most trainers who are perceived to be bullies have the capacity to change and modify their approach. We feel that most trainers value their role as teachers and that bringing trainers and trainees closer together is more likely to result in a better experience on both sides, reduce the incidences of reported bullying and ultimately improve patient care.