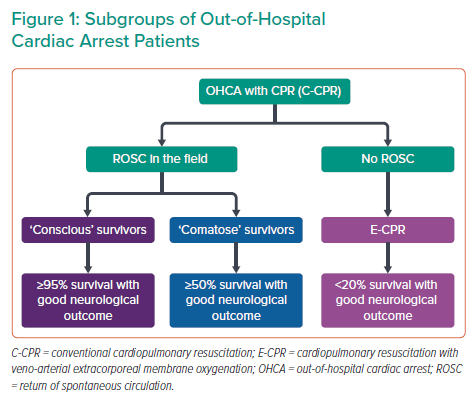

Out-of-hospital cardiac arrest (OHCA) affects approximately 80,000 patients per year in the UK, with survival to hospital discharge below 10%.1 A call to action towards a more uniform treatment strategy is much needed, and this has been addressed by the British Cardiovascular Interventional Society (BCIS) Multidisciplinary Expert Group.1 Importantly, that document clearly defines requirements for cardiac arrest centres (CACs), as well as protocols for the initial assessment and cardiovascular management of the OHCA population, which is, as recognised by the authors, very heterogeneous in terms of post-resuscitation ECG, haemodynamic status and initial neurological presentation (Figure 1).

Because ‘conscious’ OHCA survivors have no post-resuscitation brain injury and should be treated within existing acute coronary syndrome networks, the consensus document appropriately focuses on the great majority of OHCA patients with suboptimal prehospital ‘chain of survival’ and longer delays to the return of spontaneous circulation (ROSC).1,2 Because of a prolonged ‘no-/low-flow’ period, post-resuscitation brain injury occurs often and most patients remain comatose despite ROSC. The brain therefore becomes an additional, and even more important, target organ because a lack of neurological recovery is one of the most catastrophic events for patients, and represents a predominant cause of hospital death. Unfortunately, the ultimate severity of post-resuscitation brain injury, which may vary from no or mild disability to a permanent vegetative state, cannot be securely predicted at the time of hospital admission when decisions for immediate coronary angiography (CAG) and percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) are made. The authors of the BCIS consensus position statement address this issue well, and consider that this decision should be individualised by integrating known comorbidities, post-resuscitation ECG, haemodynamic status estimated by SCAI category A–E and the likelihood of neurological recovery using the MIRACLE2 score, which can be easily estimated on hospital admission.3,4 The absence of prohibitive comorbidities, ST-elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI) on post-resuscitation ECG, recurrent cardiac arrest and/or haemodynamic instability (SCAI B–E) and a realistic likelihood for neurological recovery with a MIRACLE2 score <3 would strongly argue for immediate CAG/PCI.5 In contrast, in haemodynamically stable comatose patients without STEMI, on the basis of four randomised trials, CAG/PCI can be safely deferred and performed selectively if patients develop STEMI, recurrent cardiac arrest and/or haemodynamic instability during hospital treatment.1 In the absence of such events, CAG/PCI may be delayed until the patient regains consciousness. Such a selective or delayed strategy reduces the need for CAG by almost 50% without any harm to the patients.

Although we are aware of specific circumstances related to the UK prehospital and hospital systems and understand the aim of the authors of the BCIS consensus position statement to maximise benefit and reduce futility, our concern regarding the advice to admit only patients with initial shockable rhythm and/or STEMI to specialised CACs remains unresolved. This advice particularly misses a subgroup of OHCA patients who are haemodynamically unstable and are likely to benefit from admission to a CAC because of the availability of short-term mechanical circulatory support. Furthermore, although we agree that shockable rhythm usually indicates cardiac aetiology, 20–30% of patients with a presumed cardiac cause, such as Adams–Stokes syndrome, catastrophic coronary artery disease, non-ischaemic cardiomyopathy, massive pulmonary thromboembolism and cardiac tamponade, may present with asystole or pulseless electrical activity. This is also true for the great majority of patients with non-cardiac OHCA aetiology that cannot be adequately diagnosed in the prehospital settings. Although we agree that definite scientific proof is lacking and eagerly await the results of the UK-based ARREST trial, we believe that all these OHCA patient subsets are likely to be better treated in specialised CACs, as also recommended by major international guidelines. In addition to the 24/7 availability of CAG/PCI and mechanical circulatory support, CACs have skilled intensive care units, electrophysiology, neurophysiology, imaging and specialised surgery departments, if needed.

If the currently proposed triage algorithm based only on the presence of initial shockable rhythm and STEMI is to be implemented, we advise very close communication with prehospital emergency teams that starts before patient transport, together with a low threshold for CAC admission. Furthermore, if an OHCA patient is admitted to a non-CAC, attending emergency and/or care physicians should communicate with neighbouring CACs on a 24/7 basis if a patient needs specialised interventions provided only by a CAC. Needless to say, in such cases, urgent immediate transport to a CAC should be available. For example, if a haemodynamically stable comatose survivor without STEMI on post-resuscitation ECG develops STEMI and/or cardiogenic shock after admission to a local intensive care unit, a CAC should be alerted and the patient urgently transported for immediate CAG/PCI.

Finally, we would like to emphasise that well-functioning prehospital and hospital systems for comatose OHCA patients with ROSC are also necessary prerequisites to address the needs of a much more complex and demanding OHCA subgroup without ROSC in the field (Figure 1). Currently, these patients may undergo immediate implantation of veno-arterial extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO). Despite equivocal results from currently available randomised trials, we believe this may be the ultimate upgrade of a mature high-volume acute coronary syndrome–OHCA network with interventional cardiologists responsible for percutaneous ECMO in the cath lab, followed by CAG and PCI.6–8