Coronary artery bypass grafting (CABG) has been the treatment of choice for coronary artery disease since it showed to be superior to medical therapy.1–2 Percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) emerged as a less invasive alternative to CABG and the PCI:CABG ratio has increased ever since.3

What treatment strategy is preferred for myocardial revascularisation in patients with complex coronary artery disease remains a matter of debate. It depends strongly on the complexity of the disease and patient co-morbidities, but is also a matter of the preferences of the treating physician.4 Interventional cardiologists and cardiac surgeons can be incomplete in providing information to the patient, thereby influencing the decision-making process.5 Furthermore, practice varies significantly within regions and even within hospitals in the same city.

In many patients, comparable results can be achieved either with CABG or PCI. However, some patients can only undergo CABG because they have too complex coronary artery disease deemed unsuitable to be treated with PCI. In contrast, PCI can be the only treatment option if patients are deemed inoperable due to advanced age or severe co-morbidities. The heart team – a multidisciplinary team that includes the interventional cardiologist and cardiovascular surgeon – can best weigh all the available diagnostic information and patient factors to conclude which treatment is the best for the individual patients.5–7

There are limited data on the PCI/CABG patient distribution after assessment by the heart team. Furthermore, there are very limited data from studies that investigated the outcomes of patients that are only suitable for PCI or CABG. Since this is such a selected patient population, it is crucial that separate analyses are performed. This short review summarises these data.

Trial Registries

The evidence of preferred PCI or CABG treatment for complex coronary artery disease continues to build. A large number of randomised trials have compared PCI with CABG, specifically off-pump CABG, and hybrid procedures.8–9 Trial eligibility of patients is often restricted due to specific inclusion and exclusion criteria. Therefore, numerous trials have instituted registries to characterise patients ineligible for randomisation. Through separate analysis of these patients, the overall strengths and limitations of PCI and CABG can be investigated.

The Emory Angioplasty versus Surgery Trial

The Emory angioplasty versus surgery trial (EAST) was the first to include registries alongside the randomisd treatment arms.10 The study included 842 patients of which 392 were randomised and 450 were included in the registry. The patients included in the registry were eligible to be included in the trial, but could not be randomised due to physician or patient refusal. If referred directly for CABG, patients were not approached for randomisation. If the attending or referring physician refused randomisation, the patients were also not approached.

There were several statistically significant differences between the randomised and registry patients. The complexity of coronary artery disease was higher in the registry: more lesions in total and more lesions with a total occlusion. Randomised patients were more likely to have CSS class III or IV angina, and were administered more medication (heparin, calcium antagonists, nitrates).

Which treatment the registry patients received depended on the advice of the attending physician. Twelve patients received medical management, 270 and 168 patients underwent CABG and PCI, respectively. Comparing registry patients to randomised patients, it is clear that PCI registry patients had less complex coronary artery disease deemed treatable with PCI. They had lower rates of three-vessel disease (16.7 versus 39.9 %, p<0.001) and less often had proximal left anterior descending (LAD) stenosis ≥70 % (26.8 versus 37.9 %, p=0.024). In contrary, CABG registry patients had more complex disease as shown by the higher rate of three-vessel disease (55.2 versus 39.7 %, p<0.001) and the number of narrowings ≥70 % in diameter (2.2 ± 1.3 versus 1.8 ± 1.1, p<0.001).

At three-year follow-up, survival was 95.1 % for the PCI registry and 92.9 % for the PCI patients in the randomised trial. For the CABG registry patients there was a slight improvement in survival (97 versus 93.8 %), although this did not reach statistical significance (p=0.095).

The Bypass Angioplasty Revascularisation Investigation Trial

The Bypass angioplasty revascularisation investigation (BARI) trial included a total of 3,839 patients; 1,829 were randomised and 2,010 participated in the registry.11 Similar to the EAST trial, the patients were eligible for randomisation, but refused. Whether these registry patients underwent CABG or PCI depended on the complexity of the lesions; complex patients underwent CABG.

Patients that underwent CABG in the registry had significantly more complex disease than the CABG patients in the trial, as they had more lesions (3.6 versus 3.2, p=0.001), proximal left anterior descending artery involvement (p=0.017), class C lesions (p<0.001) and diffuse disease (p=0.003). Not surprisingly, they received more grafts, had more internal mammary artery graft use, and had a higher complete revascularisation rate. In contrast, patients in the PCI registry had fewer complex lesions than the patients in the trial, with a lower number of lesions and less LAD involvement. As a result, they had more successful attempts in dilating significant lesions (p=0.019).

After seven years of follow-up, survival after CABG in the trial or registry was not significantly different (84.4 versus 85.8 %, respectively). This is not unexpected, the complexity of the disease has little influence on long-term outcomes in CABG patients.12–13 The PCI patients in the registry did significantly better than the trial patients (86.1 versus 80.9 %, respectively, p<0.01). However, this difference was no longer significant after adjustment for the worse profile of the trial patients (p=0.16). Indeed, in PCI patients the complexity of disease is significantly correlated to impaired outcomes.

The Angina with Extreme Serious Operative Mortality Evaluation

Of the 2,431 patients in the Angina with extreme serious operative mortality evaluation (AWESOME), 454 patients were randomised and 1,977 included in the registry.14 Apart from prior CABG, New York Heart Association (NYHA) III/IV classification, graft disease and left main stenosis >50 %, baseline characteristics between the trial and registry patients were similar. However, these differences were mainly because of the patients that chose not to be randomised (n=327), while the ‘physician-directed’ registry patients (n=1,650) did not show any differences as compared to the randomised cohort.

After three years of follow-up, among randomised and physician-directed registry CABG patients there was no difference in survival, survival without angina and survival without angina or repeat revascularisation. In contrast to BARI, patients in the physician-directed PCI registry had similar survival (76 versus 80 %) as the randomised patients. However, survival free of unstable angina was better in the trial (59 versus 51 %), although this did not cause more repeat revascularisation.

Synergy Between Percutaneous Coronary Intervention with Taxus and Cardiac Surgery

The Synergy between percutaneous coronary intervention with Taxus and cardiac surgery (SYNTAX) trial focused on the heart team for the decision-making process, thus the decision of the physicians.6–7 In SYNTAX a total of 3,075 patients were included: 1,800 were randomized, while 1,077 and 198 patients participated in the CABG and PCI nested registries, respectively. Therefore, physicians thought that in 58.5 % (1,800/3,075) of patients with complex coronary artery disease clinical equipoise could be met with PCI and CABG. In 35.0 % (1,077/3,075) and 6.4 % (198/3,075) only CABG and PCI were considered to be appropriate therapy.

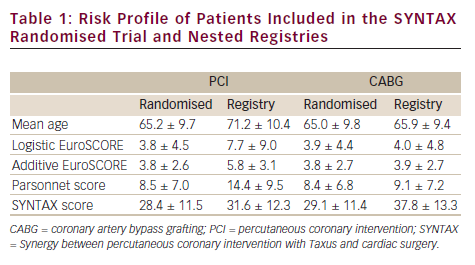

The novelty of the SYNTAX registries was that they included highly selected patients that were ineligible for randomisation. Especially the PCI registry was unique in its inclusion in comparison to other registries, as it included patients with other severe diseases, such as cancer. Therefore, the main reason for PCI registry inclusion was that patients were deemed too high-risk for CABG (71 % of the cases). For inclusion in the CABG registry the main reason was too complex coronary artery disease deemed untreatable with PCI (71 %). As compared to the randomised patients, baseline characteristics differed significantly (see Table 1). As could be expected from the reasons for registry inclusion, PCI patients were older and had a more eventful cardiac and non-cardiac history with severe co-morbidities; expressed in higher Logistic and Additive EuroSCORE, as well as a higher Parsonnet score. However, the SYNTAX score was similar. In the CABG registry it was the complete opposite: clinical factors were comparable while the SYNTAX score was significantly higher in the registry patients.

Similarly to BARI, the CABG patients in the registry did not do worse as compared to the trial patients. The rate of major adverse cardiac or cerebrovascular events (MACCE) at three years was 16.4 % in the registry and 20.2 % in the randomised CABG arm. The clinical profile of the registry and randomised patients was similar. As stated before, the complexity of lesions is shown not to increase the rate of MACCE. Thus it was not expected that these patients would do worse. On the contrary, they had slightly better outcomes. This was probably due to a higher rate of complete revascularisation, especially since the difference in MACCE was exclusively driven by repeat revascularisation.15

The PCI patients in the registry had a much higher rate of MACCE (38.0 versus 28.0 %), but this is not unexpected. First, the patients were much older. Second, both the Parsonnet score and EuroSCORE are predictors of MACCE, and the higher scores reflect their increased risk.16–18 Third, the rate of incomplete revascularisation was higher in the registry (63.5 versus 42.5 %). Lastly, 24 % of stents used were bare metal stents instead of the paclitaxel-eluting stents used in the randomised patients.

Selected Patients

The comparison of PCI versus CABG is frequently reported in randomised trials, national registries, multicentre collaborations, and single-centre experiences. However, the patients included in these analyses were either highly selected (trials), or comprehensive in the sense that they included all patients treated with PCI and CABG (national registries and retrospective studies). Not all PCI and CABG patients can be considered to be similar, as some baseline characteristics predispose better outcomes with a specific treatment (e.g. diabetes). Furthermore, the PCI:CABG ratio differs significantly per region. The outcomes of PCI and CABG in comprehensive studies are based on different revascularisation indications, decision-making, and inclusion criteria. In light of the SYNTAX registries, some retrospective studies may have included this ‘special’ cohort because no information on decision-making was available. This does reflect better the ‘real-world’ results of revascularisation, but it is crucial that separate analyses of these specific patients are available, since they represent such a different patient population.

Several papers have specifically focused on high-risk PCI patients, however, these have frequently focused on acute indications or elderly patients.18–20 These elderly patients often have a high-risk profile due to the significant contribution of age in risk models such as the EuroSCORE. 21 Therefore, based on the EuroSCORE, these studies are similar to the PCI registry, because the SYNTAX PCI registry also included patients with a high EuroSCORE. However, the patients in the PCI registry frequently had co-morbidities and concomitant diseases that are not included in the EuroSCORE. The score does indicate the high-risk profile of the cohort to a certain extent, but is likely to underestimate this in the case of the PCI registry. Therefore, PCI patients that were included in the PCI registry might even represent a higher-risk group than indicated by the EuroSCORE.

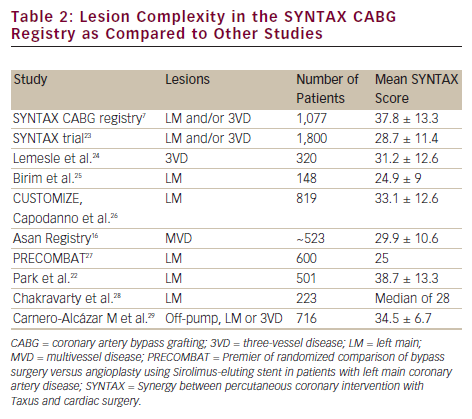

The CABG registry did not include patients with a high EuroSCORE, but predominantly included patients with a high SYNTAX score. Not many studies of CABG patients have focused on the SYNTAX score. Therefore, the ability to compare the SYNTAX CABG registry to previous reports is limited. Only the study by Park et al.22 included patients with very complex lesions similar to the SYNTAX registry, demonstrating the limited availability of data on this cohort (see Table 2).

Future Studies

The analysis of the SYNTAX registries generated new data, hopefully this is not an isolated effort. To fully understand the outcomes of selected groups of PCI and CABG patients, these should be analysed separate from the overall population. For example, patients with severe co-morbidities, a high EuroSCORE or high SYNTAX score have a different prognosis than less complex patients. However, to what extend these patients are included in ‘real-world’ analyses of large registries and retrospective studies is unknown.