We read with great interest the review entitled Best Practice in Intravascular Lithotripsy by Honton and Monsegui published recently in Interventional Cardiology.1

We fully agree with the authors on the benefits of intravascular lithotripsy (IVL), a technology that has changed the treatment of calcified lesions because of its safety and efficacy, as well as having potential advantages over other plaque modification techniques. Its main limitation is the crossing profile when treating a very tight and severely calcified stenosis where rotational (RA) or orbital atherectomy (OA) are very useful, as the authors describe.

We also believe these techniques are complementary. Indeed, we have seen with interest the growing use of the rotatripsy technique (a combination of RA and IVL) described by our group some years ago.2

However, the article does not mention the role of excimer laser coronary atherectomy (ELCA) using the ELCA catheter (Philips) as one of the techniques in the calcified lesion management algorithm.

Evidence is lacking regarding the modification of calcified plaques by ELCA. Although severely calcified plaques have been considered a hostile scenario for this technique, it is known for its good results in other circumstances, such as stent underexpansion, in-stent restenosis and chronic total occlusions, where severe calcification is the norm.3,4

Because of that, in our opinion, ELCA may play a role in the modification of calcified plaques depending on their characteristics and composition (something difficult to measure with the current technology). The results of upcoming studies such as the ROLLERCOASTR trial (NCT04181268) will shed light on this field.

In addition, ELCA is one of the most useful techniques in calcified lesions that are truly uncrossable.5 In this scenario, to perform RA or OA, a specific guidewire is needed: the RotaWire (Boston Scientific) or the Viperwire (Cardiovascular Systems). Frequently, these guidewires cannot cross the lesion directly without a microcatheter (previously advanced distally over a 0.014 inch guidewire). If even a microcatheter cannot cross the lesion, ELCA is the only possible strategy. ELCA not only modifies the plaque by itself but also can create a tunnel to facilitate the crossing of different devices. This tunnel permits devices to cross a microcatheter and the completion of the plaque modification using RA (the RASER technique) or even an IVL balloon (the ELCA-Tripsy technique), which is useful when RA or OA are discouraged or contraindicated.6,7

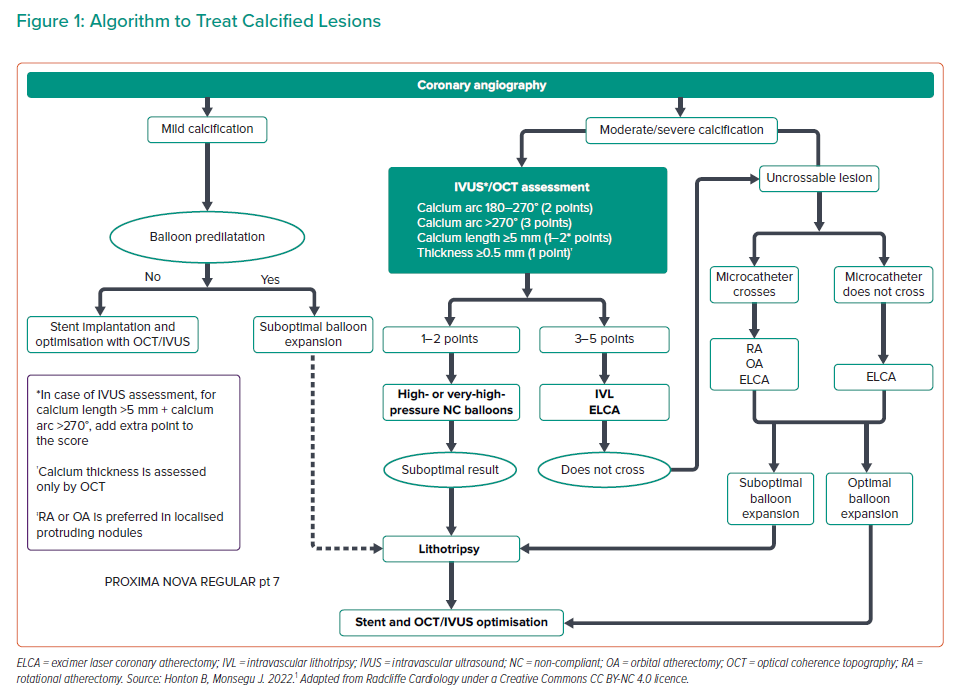

In conclusion, we agree with the authors that IVL is an easy, safe and effective technique for the percutaneous treatment of calcified coronary stenosis and is complementary to other plaque modification techniques. However, in calcified lesions that are uncrossable (even with a microcatheter), ELCA should be the strategy of choice, used alone or in combination with other techniques. Taking these factors in consideration, we propose a modified algorithm (Figure 1).