Heavily calcified coronary artery lesions hinder device delivery and limit stent expansion, which is the most relevant predictor of stent failure. This may result in low procedural success and poor clinical outcomes. Coronary angiography has a limited ability to detect calcifications when planning an optimal percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) strategy. Intracoronary imaging can provide useful insights for precise lesion assessment including a detailed analysis of the axial, circumferential and longitudinal distribution of calcium.

Physiological lesion assessment is also an important consideration to avoid unnecessary stenting, because severely calcified lesions are often associated with poor outcomes. Inadequate treatment of physiologically non-significant calcification would carry an increased risk of complications. This article aims to summarise the current data on the value of intracoronary imaging and functional assessment for coronary calcified lesions.

Intracoronary Imaging

Assessment of Calcified Plaque by Intravascular Ultrasound and Optical Coherence Tomography

Intravascular ultrasound (IVUS) imaging is based on ultrasound waves (i.e. acoustic waves) produced by the oscillatory movement of a transducer. IVUS shows calcium as echo dense (hyperechoic) with shadowing and the density is brighter than the reference adventitia. Calcium generates reverberations, especially after it has been treated with rotablation or orbital atherectomy. This is caused by multiple reflections from the oscillation of ultrasound between the transducer and calcium to create concentric arcs at duplicated distances. Dense fibrous tissue is also echo dense and sometimes even creates shadowing, but it does not create reverberations. IVUS is the most reliable diagnostic tool to detect calcium, but the leading edge of the abluminal calcium is often hidden by the calcium shadow which means that calcium thickness cannot be assessed.1

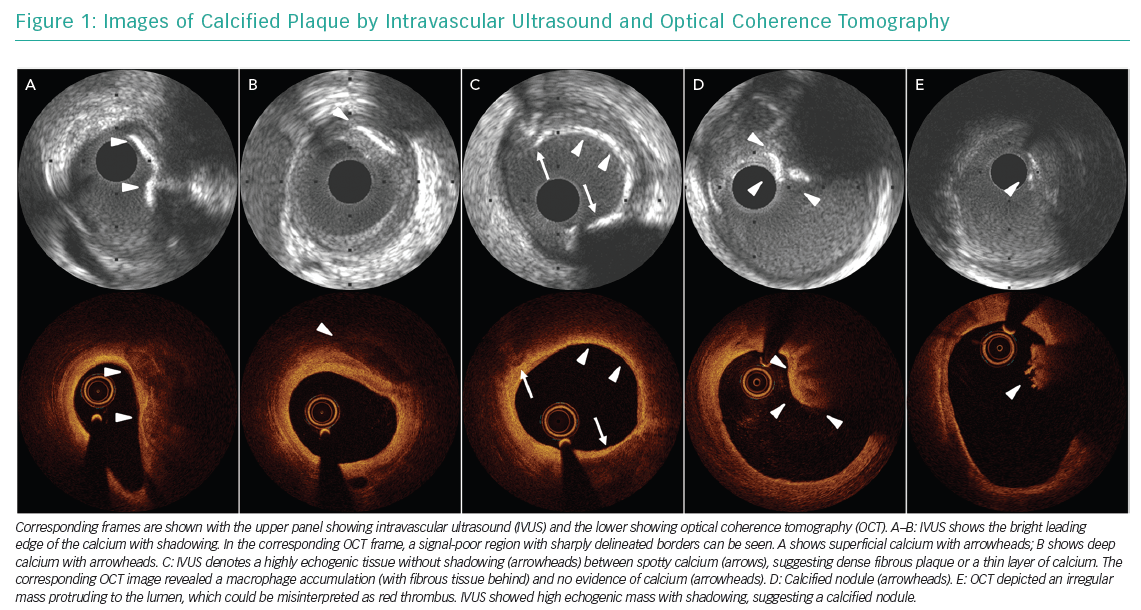

Optical coherence tomography (OCT) imaging is a near-infrared light-based imaging technique. The OCT appearance of calcium is a signal-poor region with a very sharply delineated edge and low attenuation. OCT-detected calcium is often confused with lipid, although the signal-poor regions of lipid rich tissue or a necrotic core show diffuse borders and there is substantial attenuation of the light. Erroneous categorisation of calcium as thin-cap fibroatheroma (TCFA) or macrophage is a common pitfall due to significant light attenuation behind TCFA or macrophage when calcified plaque is located at the lumen surface.2 Unlike IVUS, OCT can measure calcium thickness, area and volume. The different ways that calcium can appear using IVUS and OCT is presented in Figure 1.

In general, angiography underestimates the amount of calcium compared with intracoronary imaging. Mintz et al. reported that in a study involving 1,155 lesions, angiography detected calcium in 38% of stable lesions (n=440), while IVUS detected 73% (n=841).3 The sensitivity and specificity of IVUS for the detection of calcium, excluding microcalcifications, compared with histology (which is the gold standard for the validation) as a reference has been reported as 89–90% and 97–100%, respectively.4,5

Use of Intracoronary Imaging in Calcified Lesions

Currently, there is no standardised strategy supported by robust evidence for PCI of calcified coronary lesions. Operators decide on the use of adjunctive atheroablation based on an initial response when using the devices, such as a device unpass or a non-dilatable lesion, or they use visual estimation of calcification on angiography. In principle, plaque modification by atheroablation must be performed before stent implantation because treating stent underexpansion due to a heavily calcified lesion is challenging and should be avoided. In this context, plaque assessment with intracoronary imaging prior to stenting is more important in calcified lesions than other plaque types as poor lesion preparation directly leads to stent underexpansion. Pre-stenting intracoronary imaging delineates plaque constituents and provides accurate measurements of the minimal lumen area, lesion length and reference vessel diameters, as well as calcium arc, length and thickness, which can be used to plan procedures including adequate lesion preparation and stent sizing.

Predictors of Stent Underexpansion and Calcium Fracture

Although there is no universal guideline for plaque modification with atheroablation, there is useful evidence that provides practical guidance. Fujino et al. reported an OCT-based scoring system for patients with calcified lesion treated without atherectomy device or scoring device to predict stent underexpansion.6 In the derivation cohort of 128 patients with calcified lesions enrolled in a randomised controlled trial, a multivariable model showed that a calcium angle >180°, a maximum calcium thickness >0.5 mm, and a calcium length >5 mm were independent predictors for stent underexpansion. In the validation cohort including 133 patients undergoing OCT-guided PCI, lesions with a calcium score of 4 (lesions with calcium deposit with maximum angle >180°, maximum thickness >0.5 mm and length >5 mm) emerged as a relevant predictor for stent underexpansion.

Calcium fracture can be used as a surrogate marker for better stent expansion. A previous study of OCT including 61 patients with a heavily calcified lesion reported that calcium fractures caused by balloon dilatation were associated with smaller residual percentage diameter stenosis (19 ± 27% versus 38 ± 38%, p=0.030) and subsequent lower risk of ischaemic-driven target lesion revascularisation (7% versus 28%, p=0.046).7 These findings indicate that OCT-derived calcium parameters can guide optimal strategies for the preparation of the lesion.

Lesion Preparation According to Intracoronary Imaging Findings

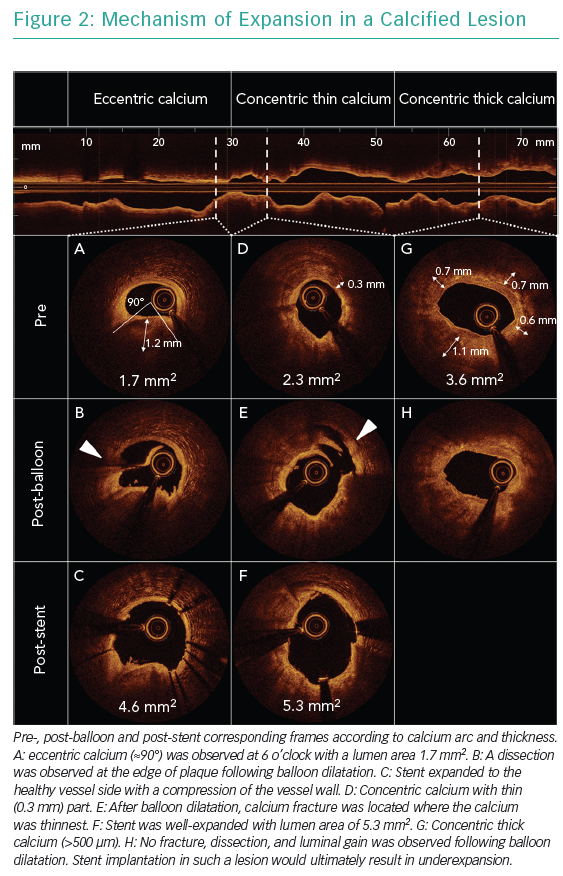

Figure 2 shows pre- and post-balloon and post-stent OCT images of calcified lesions. In general, eccentric calcified plaques (<180°) can be expanded only by means of stretching the non-calcified part of the plaques and/or creating dissection at the edge of calcified plaque, while modifications on calcified plaque may not be observed. Consequently, eccentric calcium allows for adequate stent area, although asymmetric expansion may be expected. The localisation of calcium relative to the epicardium at cross-section level should always be considered because stretching the vessel wall at the epicardium side forced by the eccentric calcium at the myocardium side may lead to an increased risk of vessel rupture. In concentric calcified lesions, high-pressure ballooning with non-compliant or scoring balloons can achieve lumen gain by creating fracture at the thinnest part of the calcium or creating dissections at the edges or in gaps in the calcium. In the presence of thick calcium deposits (>500 µm) or if no adequate balloon expansion is achieved, an atherectomy device should be considered to ablate the calcium and make it thinner, allowing the fracture of calcified plaque and further lumen gain. The use of atherectomy devices should be considered before balloon dilatation to avoid too much wire bias in principle because a wire can fit the crack created by a balloon dilatation, leading to an eccentric ablation with a risk of vessel perforation.

Atherectomy Device Selection Based on Intracoronary Imaging Findings

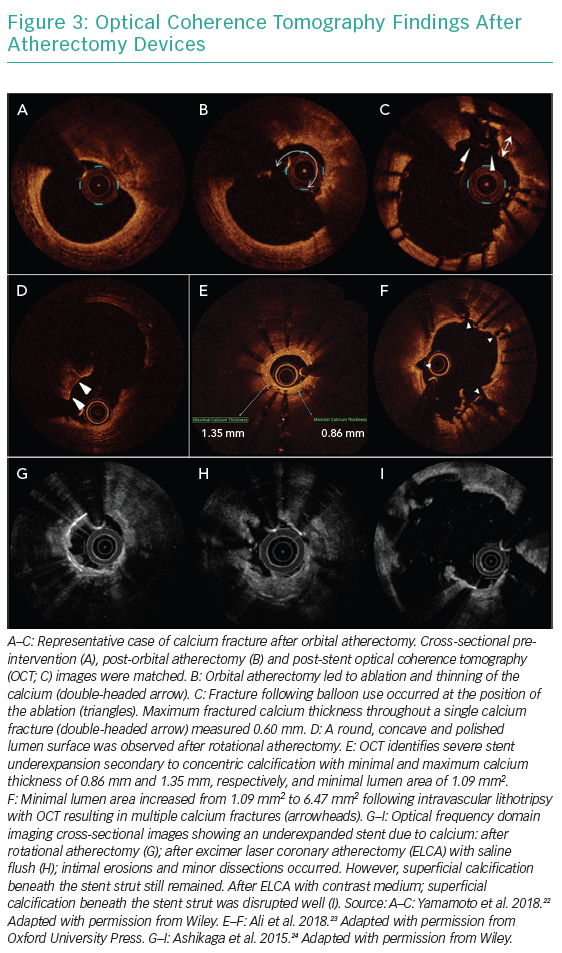

Rotational atherectomy, orbital atherectomy, lithotripsy and excimer laser coronary angioplasty can be used as atherectomy devices for coronary artery disease. Figure 3 shows OCT recordings after atherectomy by different devices. There are no randomised controlled trials comparing each device and no robust data to support one device over another. Although operators select atherectomy devices based on their preference, their expertise or local availability, findings from intracoronary imaging may help to tailor the device selection more precisely.

In general, rotational atherectomy and orbital atherectomy can effectively ablate the circumferential calcified lesion with a small lumen area.8 A retrospective observational study comparing the effect of rotational atherectomy (n=30) versus orbital atherectomy (n=30) on severely calcified lesions (maximum calcium angle >270°) reported that both devices were associated with greater calcium modifications in smaller lumens (≤4 mm2).8 Considering that the interface of rotational atherectomy is located at the tip of the burr unlike orbital atherectomy, in which the ablative crown is located 6.5 mm proximal to the tip, rotational atherectomy may be the preferred technique for lesions that are balloon impassable. Although the role of the atherectomy device on eccentric calcium lesions and calcified nodule is unclear, an assessment of wire bias may be helpful to predict the effect of plaque modification.

Intravascular lithotripsy, which applies similar principles to urologic lithotripsy which treats kidney stones using pulsatile sonic pressure waves to disrupt vascular calcium. Lithotripsy effectively modifies superficial and deep (medial) calcium without affecting soft tissue meaning deep calcium and stent underexpansion due to underlying calcified plaque can be optimal targets, although the use of lithotripsy for in-stent restenosis is not mentioned in the ‘indication for use’. Recently, a small observational study (n=30) reported that the frequency of calcium fractures per lesion increased in the most severely calcified plaques (highest versus lowest tertile of calcification severity, p=0.009) with a trend toward greater incidence of calcium fracture (77.8% versus 22.2%, p=0.057).9 Lithotripsy may lead to circumferential plaque modification and multiple calcium fracture, rather than localised tube-like effects seen with rotational atherectomy or orbital atherectomy. This results in a unique plaque modification and improved safety with lower risk of vessel rupture. Disadvantages may include it being more challenging to deliver to the lesion and a probable reduced efficacy in smaller arcs of calcium. Long-term data on intravascular lithotripsy compared with other atherectomy devices are required.

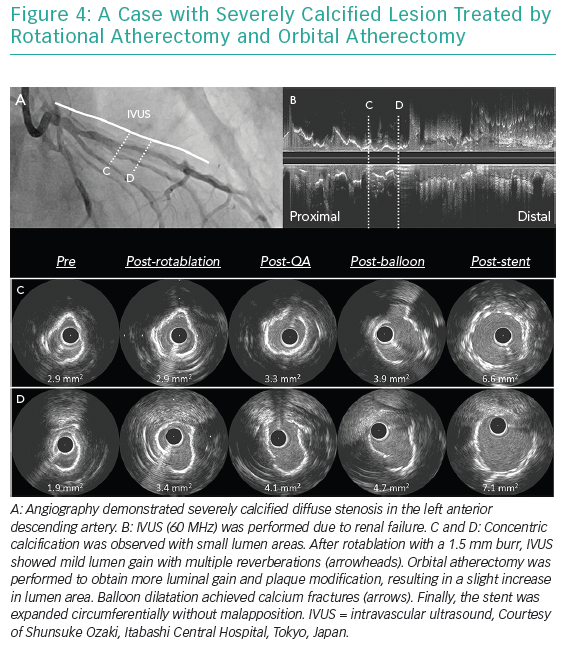

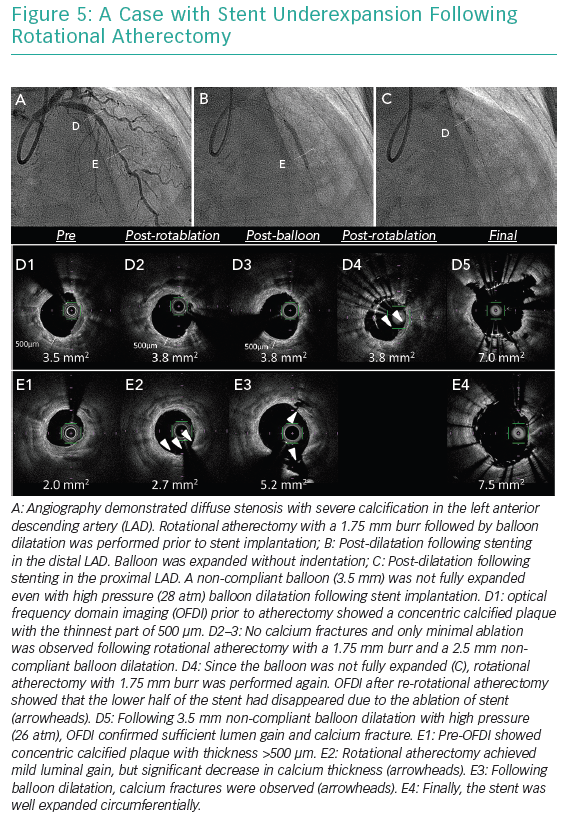

Excimer laser ablates tissues by three mechanisms including photochemical, photothermal and photomechanical effects.10–12 The laser interacts with calcified plaque predominantly by the photomechanical effect. This effect, which is increased if the laser is used with contrast injection, enables the modification of plaque underlying stents because this effect occurs beyond the direct contact. Therefore, the excimer laser is considered beneficial in case of under-expanded stents due to underlying severe calcification. Figures 4 and 5 show cases treated by atherectomy devices.

Post-stent Assessment

Stent underexpansion is a major determinant of stent failure. Stent expansion can be described as either the absolute minimum stent cross-sectional area, or the relative expansion compared with the reference area, i.e. proximal, distal, largest, or average reference area. According to the current European Society of Cardiology (ESC) expert consensus document on intracoronary imaging, absolute minimum stent area >5.5 mm2 (IVUS) and >4.5 mm2 (OCT) or relative expansion (minimal stent area/average reference lumen area) >80% are recommended.13 However, stent underexpansion can persist in calcified lesions despite several post-dilatations, therefore it is important to have adequate lesion modification prior to stenting.

Clinicians should be aware that it is more difficult to achieve uniform struts apposition in calcified lesions compared with other plaque types due to the low conformability of plaque. Although severe malapposition (axial distance <0.4 mm and <1 mm length) is one of the major targets after stenting, further expansion can lead to vessel rupture.13

Treatment Algorithm for Calcified Lesions

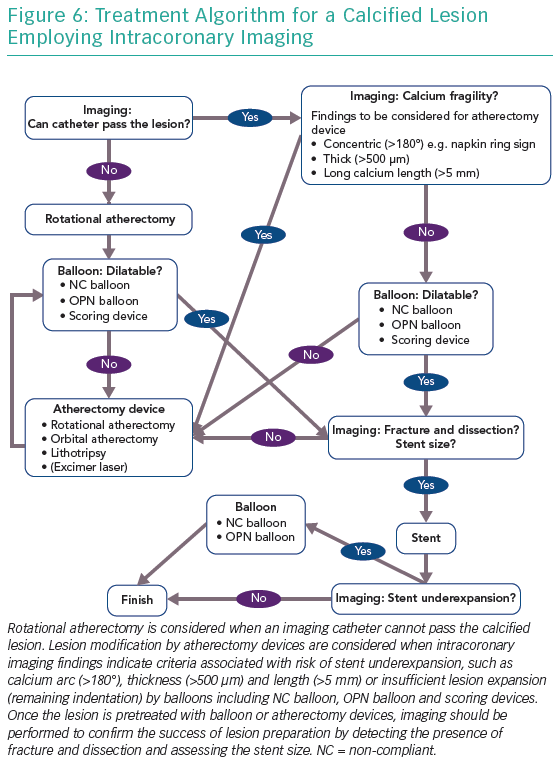

Figure 6 shows a treatment algorithm for calcified lesions using intracoronary imaging. Rotational atherectomy is considered when the imaging catheter cannot pass the calcified lesion. Lesion modification by atherectomy devices should be considered when:

- intracoronary imaging findings indicate criteria associated with the risk of stent underexpansion such as calcium arc (>180°), thickness (>500 µm) and length (>5 mm); or

- in case of insufficient lesion expansion and remaining indentation by a non-compliant balloon, OPN balloon and scoring devices.

Once the lesion has been treated with balloon or atherectomy devices, imaging should be performed to look for the presence of fracture and dissection and assess stent size and the success of lesion preparation.

Functional Assessment of Calcified Lesion

Functional assessment by fractional flow reserve (FFR) has become the gold standard for the assessment of coronary artery stenosis and has been shown to improve patient outcomes in previous large randomised controlled trials.14,15 Coronary angiography has been used to determine haemodynamic significance of given arteries; however, it is known that several angiographic factors including lesion location, lesion length, haziness, tandem lesion and bifurcation lesion are associated with positive FFR.16 There is limited data regarding the impact of coronary artery calcification on the value of FFR. In an observational study including 200 patients with intermediate coronary lesion, the correlation between angiographic severity and FFR value decreased as lesion calcification increased (none or mild calcification: R2 = 0.24; moderate calcification: R2 = 0.11; severe calcification: R2 = 0.02).17 These findings may be associated with decreased coronary artery distensibility due to the presence of coronary artery calcium. There have been several studies which investigated the relationship between defined morphological features from virtual histology-IVUS and FFR, with inconsistent results.18–20 Only one study including 48 patients with non-ST-elevation acute coronary syndrome reported that FFR correlated with necrotic core volume (r = −0.497, p=0.008) and dense calcium volume (r = −0.332, p=0.03),21 while others did not show significant correlations between plaque compositions and FFR value. Further dedicated studies with larger sample sizes are required in this area.

Conclusion

Intracoronary imaging plays an essential role in all the steps of calcified lesion treatment, especially pre-lesion assessment. Clinicians should appreciate the inherent limitations of angiography and interpret intracoronary imaging findings in combination with physiological assessment of lesion significance to improve the outcomes for this challenging patient group. Further studies are needed to test the usefulness of the comprehensive treatment algorithm including the choice of atherectomy devices based on intracoronary imaging findings in patients with severely calcified lesions.