Aortic regurgitation (AR) is a form of valvular disease with a prevalence that increases with age, such that 2% of those aged >70 years have at least moderate AR.1 Once symptoms related to AR develop, the prognosis becomes poor, with a 10–20% annual mortality rate.2 Although guidelines recommend surgical intervention, some patients with an indication for the treatment of severe AR are subsequently deemed inoperable due to comorbidities, advanced age or significant left ventricular systolic dysfunction.3,4 However, it must considered that most of the indications for treatment of aortic valve regurgitation are exclusively surgical, in particular for infective endocarditis, aortic dissection, ascending aortic dilatation, sinus dilatation and valvular tumours. In these circumstances, even if surgery may be considered high risk, the treatment is offered in the vast majority of cases.2,5 In some instances, aortic valve repair can be considered in the form of subcommissural annuloplasty, valve-sparing aortic root replacement, valve-sparing root remodelling, external annuloplasty, left ventricular outflow tract suture and root restoration.2

Despite surgery being a viable option in patients with AR, there is an unmet need for a percutaneous procedure, particularly in patients at high or prohibitive surgical risk, which could be as feasible and successful as transcatheter aortic valve implantation (TAVI) in patients with aortic stenosis.

In fact, for patients with pure severe AR without stenosis and at prohibitive surgical risk, TAVI is occasionally performed, but it remains a significant clinical challenge.6 Although AR due to extreme aortic root or annular dilation, infective endocarditis, aortic dissection and valve tumour is an absolute contraindication to TAVI, when the AR is due to failure of leaflet coaptation TAVI may be considered.7 However, the main issue is the absence of valvular calcium. An elegant review of the pathological correlation of aortic valve leaflet features (post-surgical explant) demonstrated that AR, unless secondary to congenital bicuspid aortic valve disease, is rarely associated with calcium deposits.8

The following are the various aetiologies of pure AR:

- Systemic hypertension

- Congenital bicuspid

- Active or healed infected endocarditis

- Rheumatic disease

- Aortic dissection

- Collagen disease

- Reiter’s syndrome

- Ankylosing spondylitis

- Syphilis

- Prolapse secondary to ventricular septal defect

- Trauma

- Prolapse

- Sub aortic syndrome

- Marfan syndrome

- Rheumatoid arthritis

Another factor that makes TAVI challenging in AR is the presence of aortic root dilatation. This often does not represent a significant challenge in aortic stenosis because the calcified leaflets can still hold the TAVI device in place.6

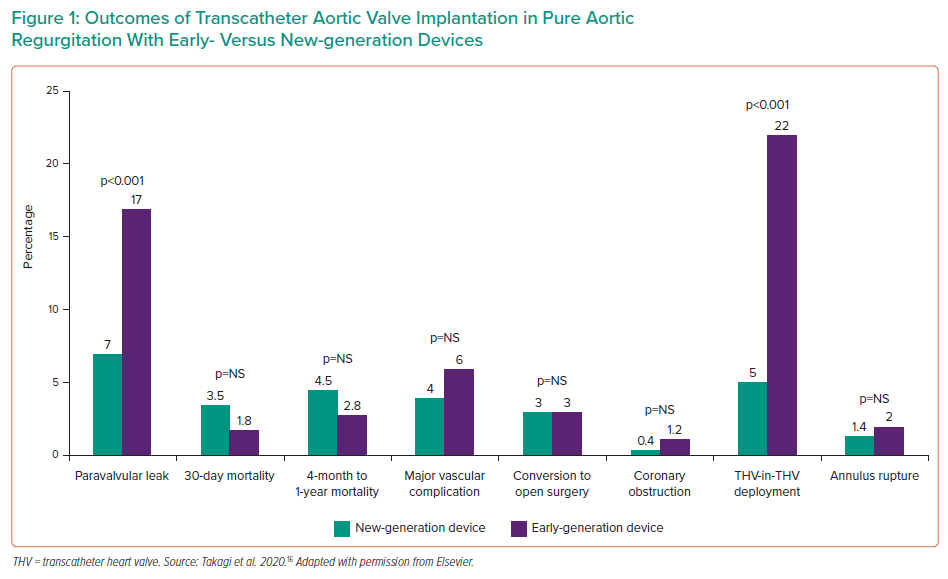

The larger stroke volume in AR compared with aortic stenosis makes device positioning and deployment unpredictable, with a tendency to prosthesis embolisation or malposition, which can be either into the aorta or into the left ventricle up to several hours after the procedure (Table 1).9

Prosthesis oversizing is routinely performed to mitigate the risk of valve migration. A 15–20% oversize is recommended when selecting the device size, with caution not to go beyond that to reduce the risk of annular rupture or pacemaker requirement.10,11

TAVI in Pure Severe Aortic Regurgitation With Non-dedicated Devices

With first-generation devices, outcomes were particularly poor due to valve embolisation, residual AR and the need for a second valve.6

In particular, in the first series of TAVI in pure severe AR, 43 patients were treated with CoreValve (Medtronic) and two pigtails catheters were used in different sinuses of Valsalva to better identify the annulus.12 Although the success rate was 97%, in 19% of cases a second valve was required during the index procedure.12

Several studies were then published using CoreValve (Medtronic) and other first-generation devices, such as the Sapien valve (Edwards Lifesciences).13,14 The results of these were summarised in a meta-analysis in 2016 including 237 patients with severe pure AR treated with TAVI. Procedure success ranged from 77% to 100%, with a 7% risk of implantation of a second device due to prosthesis migration or severe procedural AR.14

Some of these first-generation devices were updated with new features that aimed to improve retrievability for the self-expandable devices and an adaptive seal for both self- and balloon-expandable devices.6

These second-generation devices have been compared to first-generation devices in case series studies. In a multicentre study with 254 patients, the overall device success according to Valve Academic Research Consortium (VARC-2) was 82% with second-generation devices, compared with 47% with first-generation devices.13 This was the result of less valve malpositioning, less significant severe post-procedural AR and less cardiovascular mortality with second-generation devices. Interestingly, device embolisation happened in cases of under- or oversizing of the devices.

Similarly, in another study, Yoon et al. collected a series of 331 patients from 40 centres and compared first- and second-generation devices.6 Overall device success was 74%, again driven by a lower rate of post-procedural AR and valve embolisation. In that series, the absence of calcium was a predictor of unsuccessful valve deployment in the case of first- but not second-generation devices. Very large annuli (>25 mm) were associated with less device success for both first- and second-generation devices. Finally, valve oversizing at least of 15% was associated with less frequent residual significant AR.6

The third multicentre series available comparing second- and first-generation devices included 78 patients with severe pure AR.15 Essentially, the results of that study replicated the findings of the other two series, with greater procedural success for new-generation devices, with less embolisation and less residual post-procedural AR.

Although the newer-generation TAVI devices have improved these outcomes, they remain suboptimal compared with TAVI for aortic stenosis, highlighting the need for dedicated transfemoral systems for treating pure AR that provide robust annular anchoring in the absence of aortic valve calcium.6

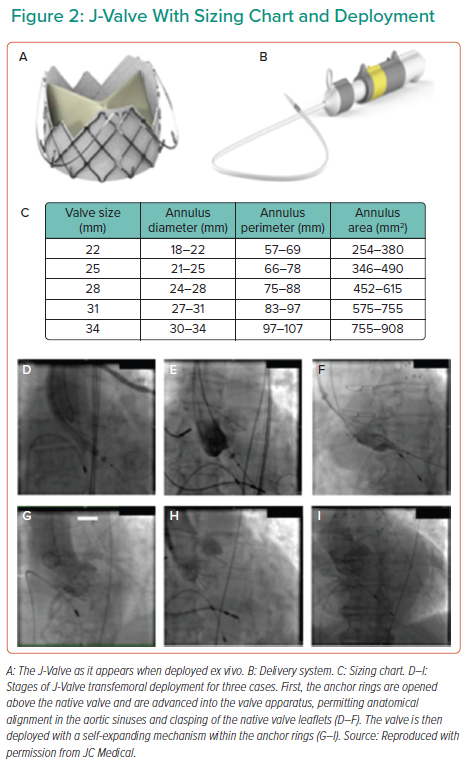

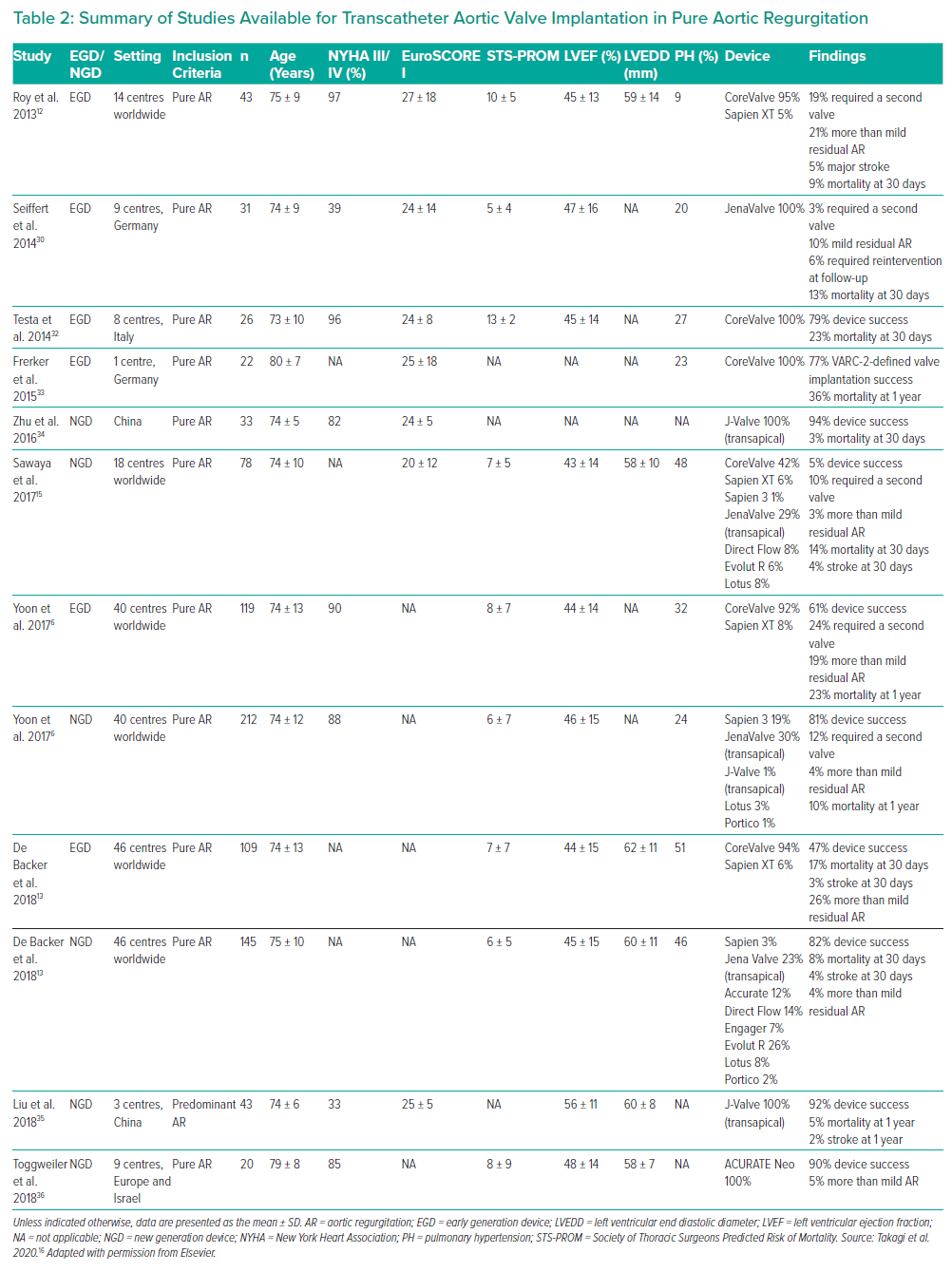

Takagi et al. analysed all these available studies, the feature of which are described in Table 3, finding that the success rate for new- and early-generation devices was 90% and 67%, respectively.16 New-generation devices also performed significantly better in a variety of outcomes, including paravalvular leak, short- and medium-term mortality and major vascular complications.16

The available studies are summarised in Figure 1 and Table 2.

TAVI in Pure Severe Aortic Regurgitation with Dedicated Devices

To date, the only two dedicated transcatheter valves for AR are the J-Valve (JC Medical) and the JenaValve (JenaValve Technology). Both devices have been used successfully via the transapical approach.17,18 However, transfemoral experience is limited to first-in-human publications.19,20 These devices have not been approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA), but the former is available under ‘expanded access’ for compassionate use (NCT03876964) and the latter is under investigational device exemption evaluation in a clinical trial (NCT02732704), both only as transfemoral devices.

J-Valve

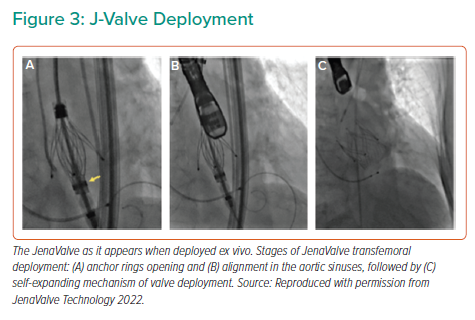

The J-Valve consists of a porcine aortic valve within a self-expandable nitinol stent and three U-shaped ‘anchor rings’ (Figure 2A) that is deployed in a two-step process. The valve is delivered by an 18-Fr steerable delivery system (Figure 2B). The valve cannot be recaptured and is currently available in five sizes (Figure 2C). It is chosen according to annular sizing, aiming to a 10% oversizing for the AR indication.

Once the J-Valve is brought into the ascending aorta, the anchor rings are opened above the native aortic valve and advanced, permitting anatomical self-alignment in the aortic sinuses and clasping of the native valve leaflets (Figures 2D–2F). The valve is then deployed, without the need of pacing, with a self-expanding mechanism within the anchor rings, capturing the native leaflets (Figures 2G–2I), aiming for a final position being 70% aortic and 30% ventricular relative to the annulus.

Certain unique features of the J-Valve seem to solve the issue of valve embolisation. In particular, the self-aligning anchor rings, together with the self-expanding valve, directly grasp the aortic valve leaflets, providing solid anchoring. In addition, once the anchor rings are positioned in the aortic sinuses in the first stage of the deployment, the subsequent position of the valve can still be adjusted coaxially to the annulus prior to valve deployment. Indeed, among 47 patients with AR treated by transapical implantation of the J-Valve, no valve embolisation occurred.18,21 Another advantage of the J-valve deployment sequence is the lack of rapid ventricular pacing. This may be particularly beneficial in patients with severe AR because, when referred for TAVI, most of them have at least moderate left ventricular systolic dysfunction and heart failure.6

It has been suggested that the novel J-valve leaflet grasping system could potentially reduce the risk of coronary obstruction in high-risk cases.22 However, coronary obstruction has also been reported in a case of transapical J-Valve.23 In this case, the mechanism was attributed to balloon valvuloplasty prior to valve implantation. In particular, the authors reported that the leaflets were torn along the aortic annulus and the valve was divided into a small non-coronary cusp and a large left-right cusp that was squeezed between the implanted valve and the anchor rings, eventually causing right coronary artery obstruction shortly after implantation of the J-Valve.23

In terms of durability, Li et al. recently reported on the 4-year follow-up of 18 patients treated with transapical J-valve implantation (14 for aortic stenosis and four for pure AR).21 In patients whose indication for TAVI was AR, the mean gradient did not increase significantly from discharge to the 4-year follow-up, remaining <10 mmHg with no residual valvular or paravalvular AR. In contrast, patients whose indication for TAVI was aortic stenosis had stable mean gradients, but 14% developed moderate valvular regurgitation at the 4-year follow-up.21 In light of these data, more studies are warranted regarding long-term durability of the J-Valve.

In terms of valve anatomy, it must be considered that certain morphologies, such as type 0 bicuspid aortic valve characterised by the absence of raphe, may be a relative contraindication for the implantation of the J-Valve due to a suboptimal anchoring mechanism of the three anchor rings, specifically designed for a trileaflet valve.21 Finally, it must be considered that although the J-Valve may be feasible for a maximum annular area of 908 mm2, pure AR due to extreme root or annular dilatation will remain a contraindication for TAVI with the current technology.

JenaValve

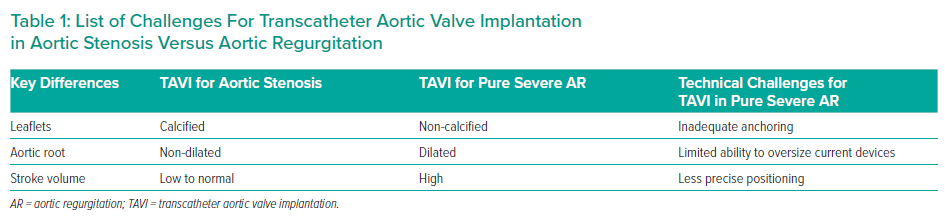

The JenaValve (JenaValve Technology) is a porcine root self-expanding valve on a nitinol frame with three integrated locators (previously called ‘feelers’), similar to the J-Valve, and a sealing ring of 24 diamond-shaped cells. The locators align the device with the native valve leaflet anatomy and act as a strut onto which the nitinol frame is expanded, essentially clipping the device to the native leaflets (the engagement step). This engagement mechanism allows anchoring of the valve independent of cusp calcification, therefore making it an ideal design for treatment of pure AR (Figure 3A).

The JenaValve has undergone iterations since its first in-human implantation in 2011.24,25 Initially only a transapical technology, case series in aortic stenosis patients suggested success rates of between nearly 88% and 100% with a low incidence of moderate paravalvular leak (4%).25–27 Subsequently, the Jupiter Registry, analysing 180 implantations, reported procedure success of 95% with no annular rupture or coronary ostia occlusion, with only 2% of patients showing moderate or above paravalvular AR at the 1-year follow-up.28 However, the need for permanent pacing was high, at nearly 20%.28

In pure AR, various cohort studies have been performed using the transapical system. Schlingloff et al. reported 10 implants with a 100% success rate, with amelioration of AR in six and trace or mild AR left in the other subjects.29 Again, the pacemaker implantation rate was high at 20%.29 In a larger subsequent study, 30 of 31 transapical implants were successful (a valve-in-valve bailout for dislodgement was needed in the unsuccessful case), with no or trace AR in 28 and mild AR in the others, suggesting that the underlying JenaValve design and engagement mechanism are safe and haemodynamically effective.30

Following a redesign of the introducer system, the JenaValve has been converted to allow for transfemoral implantation, whereas the transapical device is no longer available. The first in-human transfemoral JenaValve implantation was successfully performed in 2017 for pure AR.19 The implantation technique involves positioning a 19 Fr hydrophilic sheath into the ascending aorta to allow for valve delivery, with deployment steps similar to those for the transapical version (Figure 3B). In AR patients, a 10–20% valve oversizing to annular dimension is recommended for adequate sealing. The transfemoral system is currently under investigation in two trials, one for AR (ALIGN-AR) and one for aortic stenosis (ALIGN-AS), and is not currently available for use outside of trial settings (NCT02732704, NCT02732691).

In 2019, preliminary data from the ALIGN-AR trial were presented at Transcatheter Valve Therapeutics. By then, 37 patients had been enrolled between the US, Germany and the Netherlands.31 The primary completion date for the ALIGN-AR trial was estimated to be by the end of 2021, with an estimated enrolment of 50 patients. However as per May 2022, the completion date is still pending. Of the 37 patients enrolled in 2019, 12 had the procedure performed; for these 12 patients, the mean (±SD) age was 75 ± 7 years, the mean Society of Thoracic Surgeons score was 3.5 ± 2.1 and the left ventricular ejection fraction was 53 ± 8%. A size 27 (the largest) valve was implanted in 67% of patients. Technical success was achieved in 11 patients, with one patient having to be converted to surgery. No patient had more than mild residual paravalvular leak and none had coronary occlusion.31

Conclusion

In summary, TAVI for severe pure AR with new-generation non-dedicated devices is feasible, with an acceptable risk of complications. Percutaneous intervention should be considered after careful patient evaluation by the heart team, when the surgical risk may be too high.

Dedicated devices show a promising future for TAVI in severe pure AR. The definitive results of the ALIGN-AR (NCT02732704) with the JenaValve will hopefully provide a further step forward in percutaneously treating this condition.